This essay is in support of Field Guide, an online exhibition curated by Jason Bailey that opens on Feral File on January 20th, 2022 at 9 am ET.

Before they go into the water, a diver cannot know what they will bring back. —Max Ernst

Digital art, and specifically generative art, is exciting for its ability to dramatically open up possibilities for artists looking to discover and share new worlds. Exploring hundreds of variations of a single image or theme using analog tools for drawing and painting can take years or decades. With computing and digital tools, we have the ability to rapidly generate near-infinite variations, exploring ideas faster and deeper through systems of our own design.

Rather than act as a mirror, dutifully recreating or reporting back on the world around us, these artists often act as a portal to an entirely new universe. A universe where the artist has crafted unique entities from scratch through many compressed cycles of evolution. A universe where fascinating beings and impossible environments blend the foreign and the familiar, giving us a sense that there is life here, but perhaps not life as we’ve known it.

For Field Guide, I’ve curated a selection of artists, each with their own distinct aesthetic, but all of whom I believe share a circuitous process of artistic discovery and a remarkable ability to breathe life into new forms. As a curator’s prompt, and in a nod to the new life and habitats created with generative art, I’ve asked the five artists to create a set of two new works around the ideas of “specimen” and “ecosystem.”

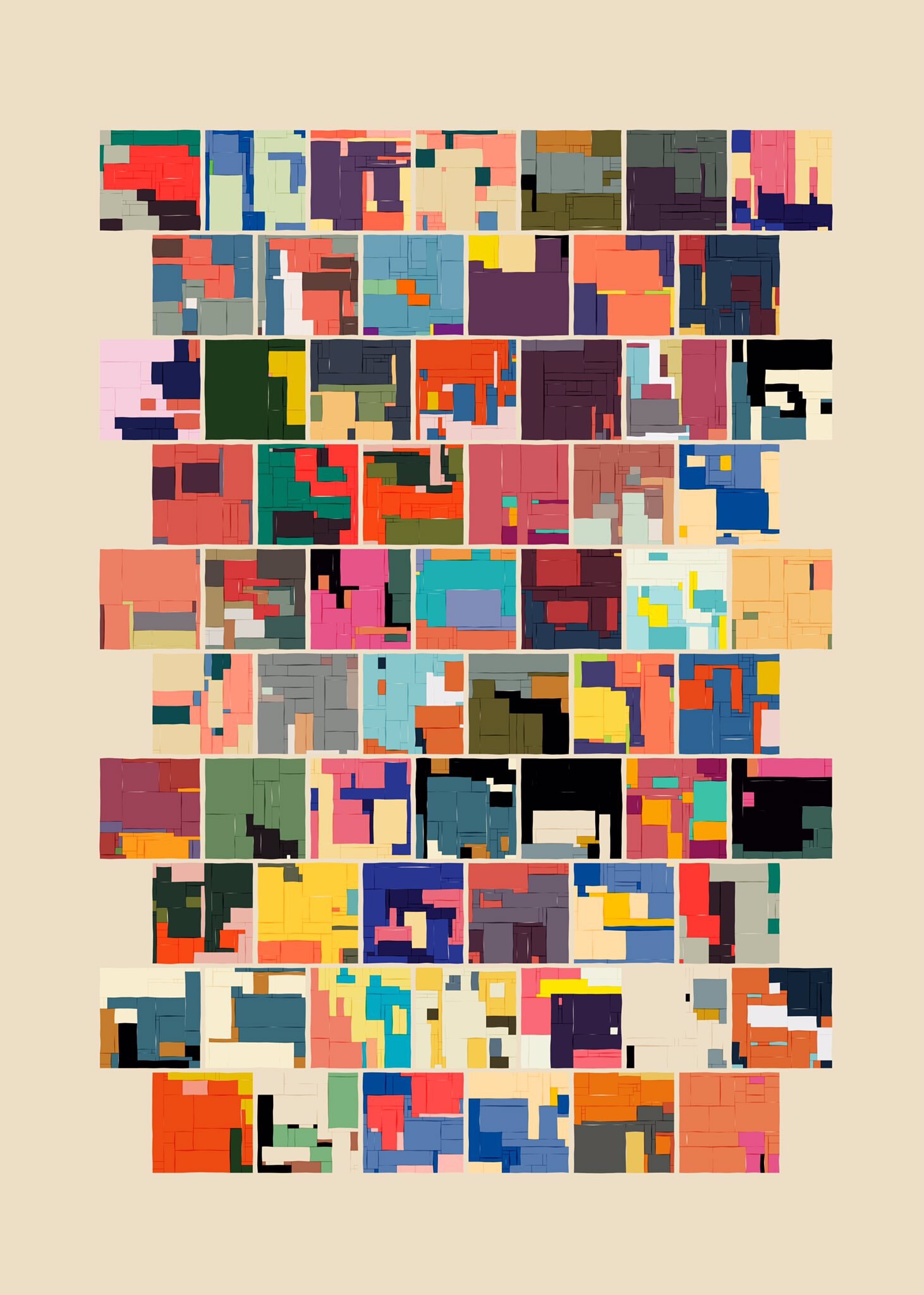

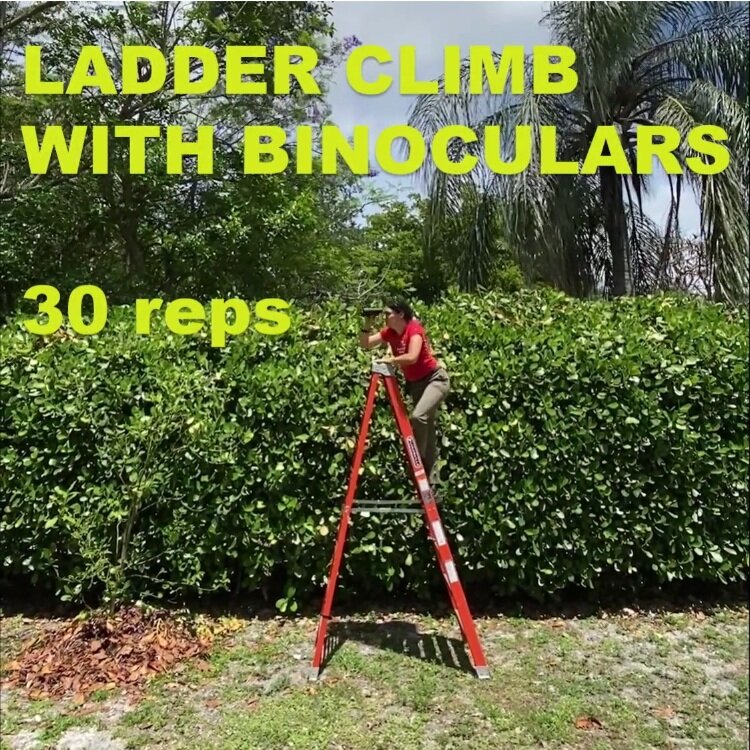

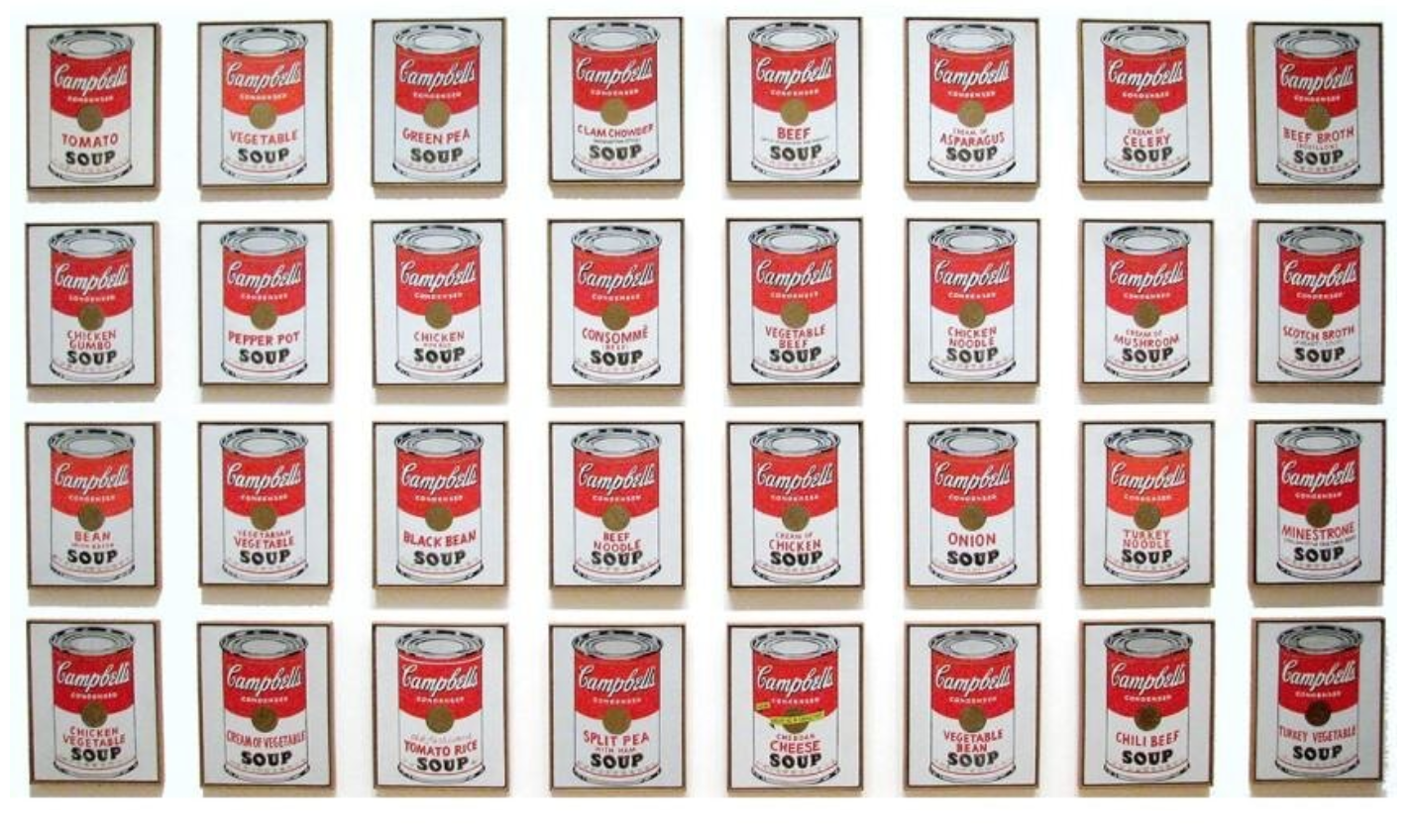

In this show, I wanted to focus on the artistic process for each artist, highlighting how the proliferation of work afforded by digital tools often leads the artist to spend as much time curating as creating. However, it can be hard for the viewer to gather much context when looking at just one or two works by an artist. So as part of my prompt, I also asked them to leverage Edward Tufte’s concept of small multiples. Small multiples display a set of images in close proximity to each other, typically in a grid-like pattern, to facilitate comparisons across the full group of images at a glance.

While small multiples is a concept borrowed from the field of data visualization and information design, it is a technique often adopted knowingly (or unknowingly) by artists seeking to share process and evolution in a single image. From an interview I conducted with Jared S Tarbell in 2020:

Another particularly powerful lesson I learned from Tufte was small multiples, which applies to generative systems. You can build this machine that generates an infinite number of forms, but all very similar forms. But how do you show [people] what the machine is doing…? The way to do that is by just laying small multiples right next to each other. When the outputs of the machine are all next to each other, you get an idea that this is a system — this isn’t a single image.

With Field Guide, I was hoping the simple prompt around “specimen” and “ecosystem” combined with the display of small multiples would provide unifying conceptual and aesthetic guardrails without dampening the artists’ creativity. I couldn’t be more thrilled with the work the artists came back with.

Iskra Velitchkova

The NFT explosion this year has created an arms race toward increasingly loud and fast-moving digital imagery jockeying for attention (and sales). Against this backdrop, Iskra Velitchkova’s work stands out in contrast to all the noise for how quiet, subtle, and meditative it is.

Velitchkova is an artist currently based in Madrid. Her work explores the present and potential interactions between humans and machines, and how instead of making technology more human, this relationship can push us to better understand our limits. She believes that roots and tradition can nurture her work with greater truth. After a stint in the tech and artificial intelligence industry as a visual thinker, Velitchkova decided to apply her knowledge and experience to her own research using art as a medium for generative explorations. Her work is based on mixed techniques: both digital and physical.

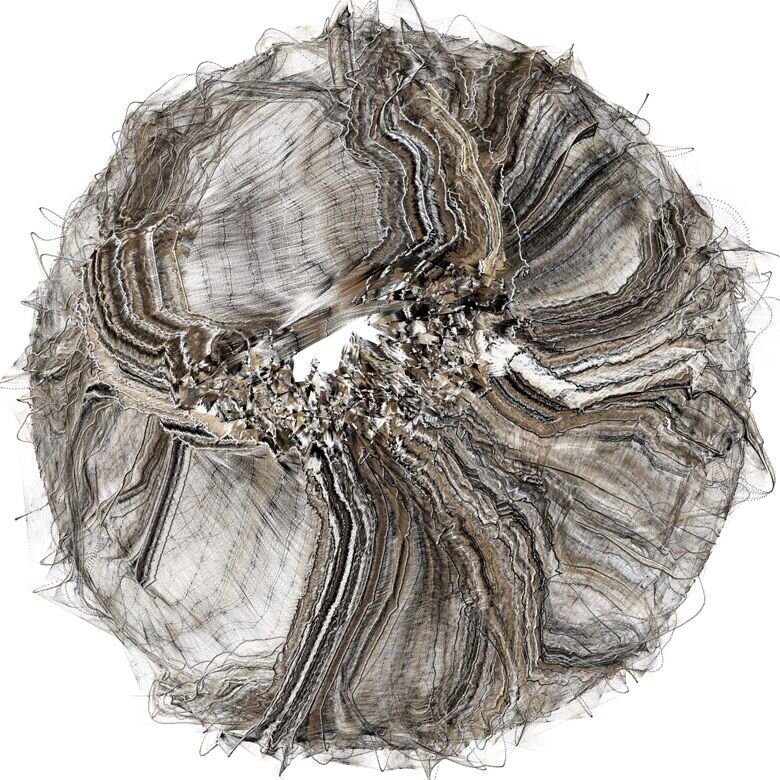

Hypothetically Micro, Iskra Velitchkova, 2021

Hypothetically Micro confronts us with a dozen bold ribbon-like entities placed against flat backgrounds of solid color. Familiar on the surface, they become increasingly difficult to place, particularly in terms of scale. Velitchkova’s lyrical specimens are artfully cropped in a way that suggests we may be looking at the tail, wing, fin, or frond of a much larger organism. Yet, something about the color palette also recalls the dyes used in microscopy: These forms could just as easily be microorganisms as they could larger birdlike or fishlike creatures. Her work shines next to other generative artists for its elegant biomorphic forms and subtle exploration of color. Velitchkova is a magnificent biological architect, painstakingly crafting visual systems while bringing delicate new creatures to life.

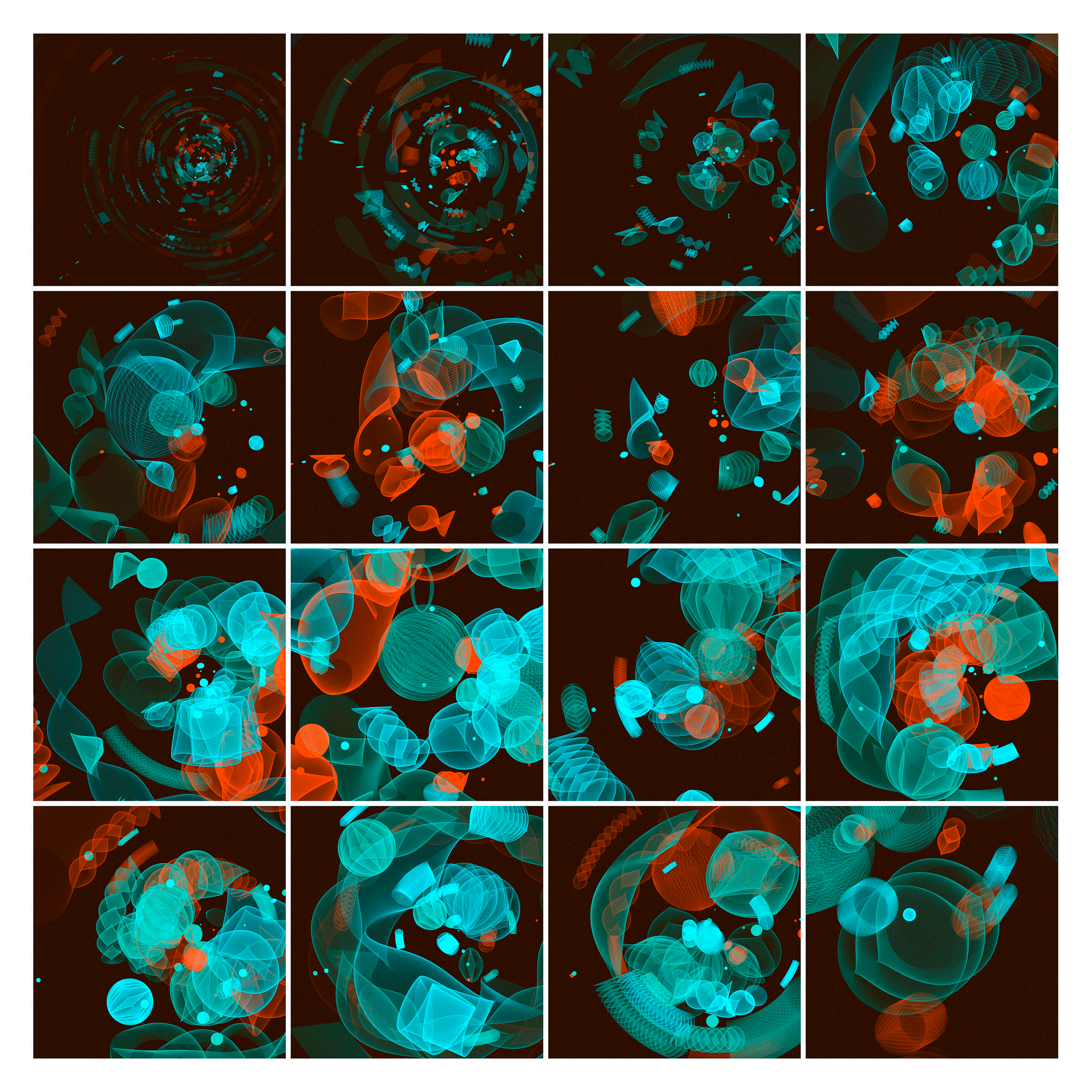

Hypothetically Macro, Iskra Velitchkova, 2021

Hypothetically Macro is a mysterious cluster of glowing semitransparent organic primitives. The artist leverages the Processing programming language to deeply explore several variations of a single visual theme. Exploring the creation of new worlds through generative algorithms, Velitchkova presents us with images that could just as easily be on the other side of a microscope as they could a telescope. One might seem like a nucleus with quasi-biological elements embedded into a transparent cytoplasm at one minute, and the next, a celestial body with an orbital structure and a background of infinite darkness. The grid reads almost like an animatic or a storyboard propelling us through a single ecosystem frame by frame.

Ilya Shkipin

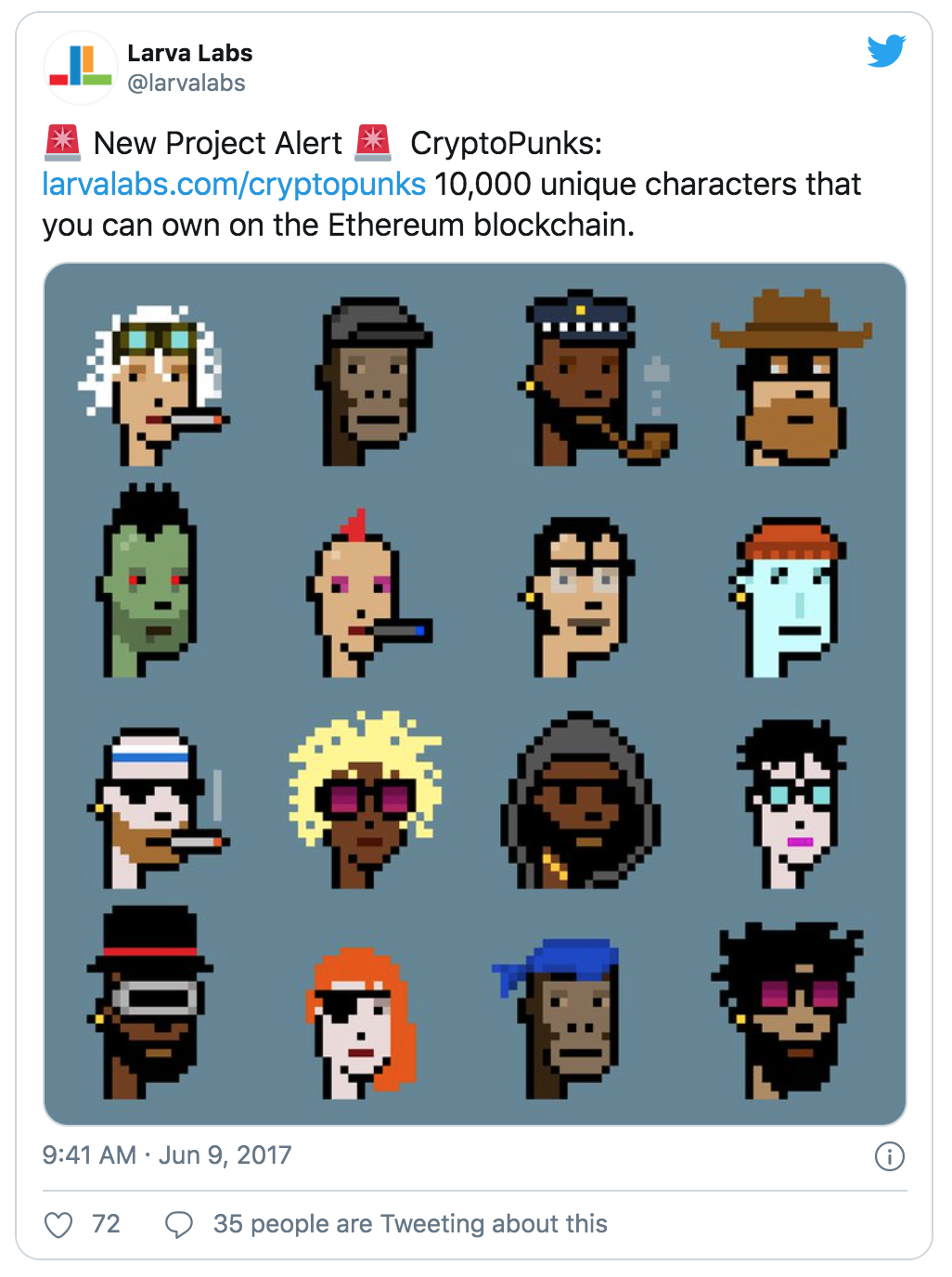

By mid-2021, despite my best efforts, I found it almost impossible to ignore the avalanche of cutesy PFP (personal profile pic) NFT projects featuring cartoon apes, cats, penguins, etc. Around that same time, generative art also captured the public’s eye, but sadly, it, too, quickly devolved, turning into a flood of hastily constructed, hard-edged geometric abstractions produced to meet the new market demand.

Never had I been surrounded by so much imagery that left me feeling so flat. I found myself craving the grotesque. I wanted to be shaken, made to feel uncomfortable, made to feel… anything, really. It was about this time that I discovered the work of Ilya Shkipin. His work makes me feel like I blacked out in a cheap motel room and woke up to find Polaroids under a dirty ashtray documenting the bad life decisions from the night before. Yet it also has its own deep sense of beauty.

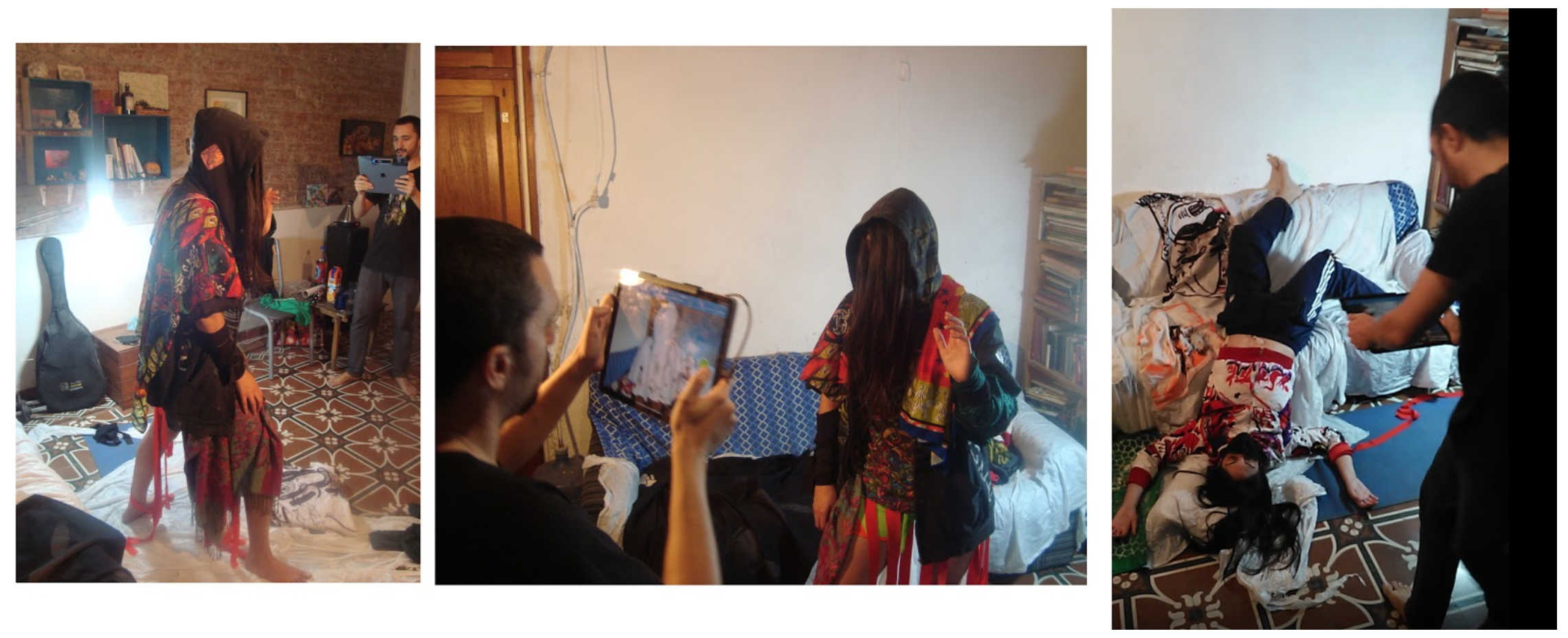

Shkipin is a classically trained artist that received a bachelor’s degree in illustration at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco. For many years, he has experimented with expressionistic figurative painting, and he worked as an artist in the Bay Area before incorporating neural networks into his work. He uses various neural networks such as VQGan, Clip, and Styletransfers to achieve his vision to “disturb the comfortable and comfort the disturbed.” With his work, Shkipin explores the blending and deconstruction of a figure through abstraction, kind of like how dreams deconstruct forms and memories.

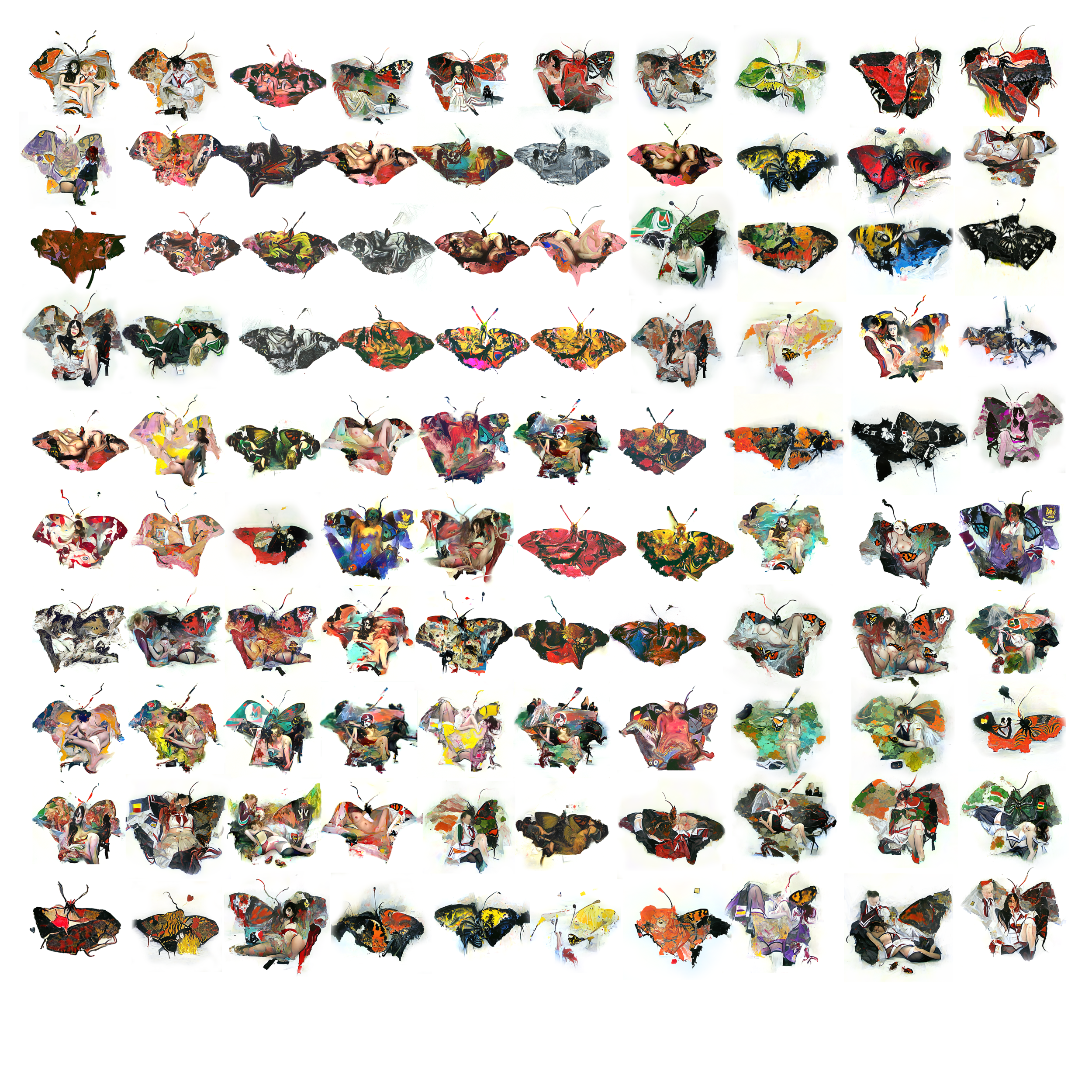

Blooming Valetudinarian, Ilya Shkipin, 2021

Blooming Valetudinarian is a stunning interplay between attraction and repulsion. As a group, the forms read as 100 beautiful winged insects, a diverse entomological collection of moths or butterflies. But upon closer examination, many of the butterflies reveal a surreal vignette of entangled biomorphic forms that feel voyeuristic, if not bordering on pornographic. Shkipin’s specimens elicit unsettling emotions similar to works from Egon Schiele or Francis Bacon. The images pull in just enough elements from reality to hint at the familiar, while largely leaving us on our own to fill in the blanks. The emotional resonance, compositional awareness, and sensitivity to color brought by Shkipin highlight what neural networks like CLIP are capable of when placed in the hands of a true artist.

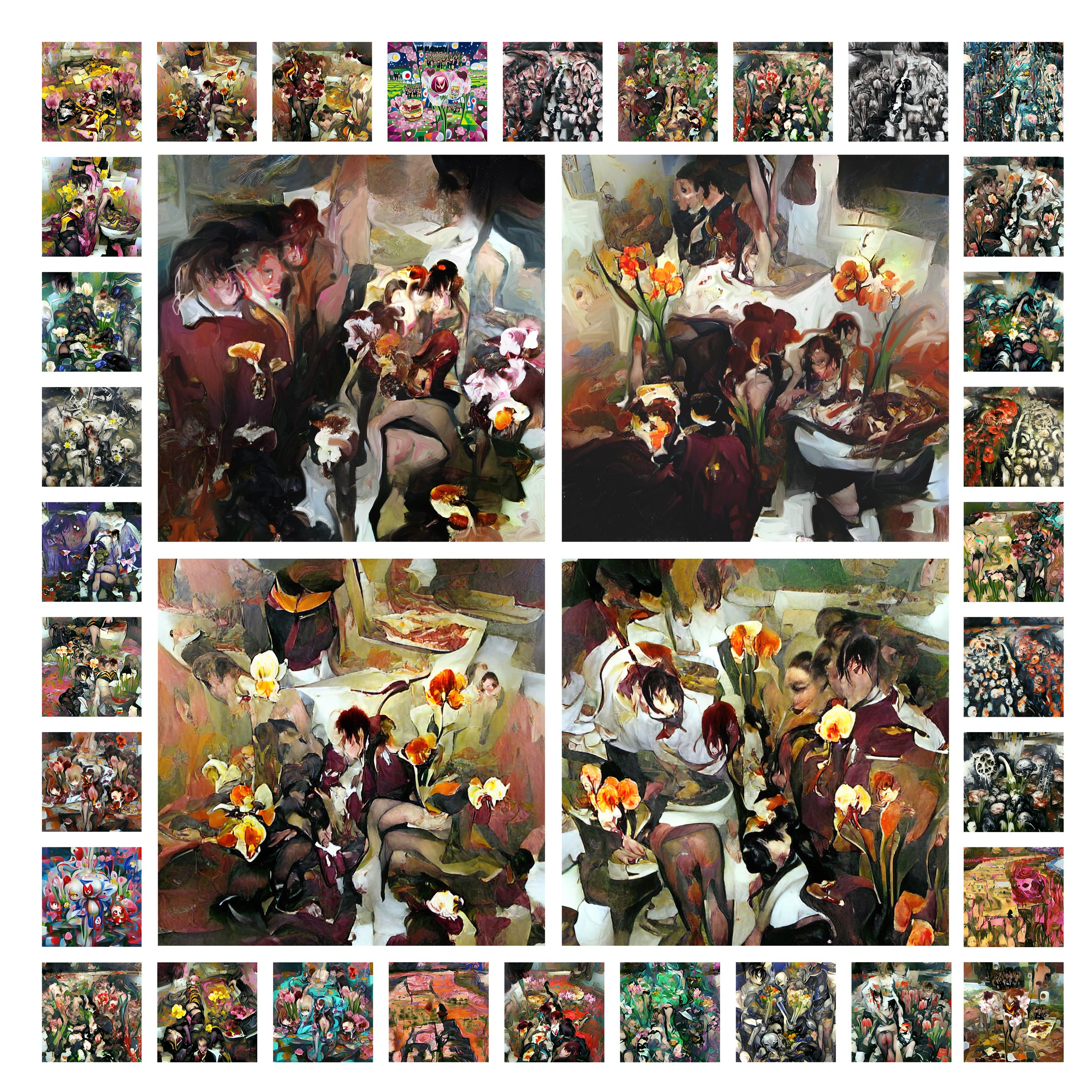

Malade Imaginaire, Ilya Shkipin, 2021

Malade Imaginaire appears to be a lovely mosaic of vibrant gardens, a logical environment for Shkipin’s butterfly-like specimens from Blooming Valetudinarian. But planted alongside the abstract floral structures are twisted limbs and biomorphic forms that belie the serenity of a calm and peaceful garden. Given only partial and conflicting visual information, we struggle to place the proper emotional response, forcing us to spend additional time deeply examining the artist’s individual ecosystems. Shkipin leverages the popular neural network CLIP to generate his images; however, this is just a starting point. Leveraging his classical training as a painter, the artist then painstakingly retouches each carefully curated image to achieve the desired effect.

Sasha Belitskaja

Sasha Belitskaja is an Estonian architectural designer, NFT artist, and UX developer whose work centers on novel interactive design models and the interplay of new emergent aesthetics. Her projects focus on utilizing computer graphics and game engine technology to explore new forms of connectivity between audience, creator, and community. She received her bachelor of architecture from the University of Dundee, graduating with distinction, before continuing her master’s studies at Die Angewandte in Studio Greg Lynn.

As with several other artists in this show, I first discovered the work of Sasha Belitskaja on HEN (Hic et Nunc), a rich platform for digital artists that blossomed in early 2021. I fell in love with a series of pulsing abstract forms she created that felt like invented human organs. As such, I knew she would be a great fit for this exhibition.

Belitskaja brings a unique perspective to the Field Guide exhibition as an artist with a background in architecture working primarily in 3D. Thinking more spatially, almost in terms of building blocks, Belitskaja’s work stands out for its mechanical aesthetic and playfulness.

In Search of Your Digital Self, Sasha Belitskaja, 2021

In Search of Your Digital Self lightheartedly explores the trend toward people becoming increasingly emotionally (and financially) invested in their metaverse avatars. Injecting a welcome sense of humor into the exhibition, Belitskaja presents us with an army of twelve curious bots, each with their own distinct biomechanics, marching toward the viewer in lockstep. Though we typically think of machines as being designed to perform specific tasks or work, the artist’s bots feature quirky plumage and imaginative ornaments that appear to serve no purpose other than self-expression. Each has its own sense of fashion, though most appear to be wearing the same shade of lipstick, perhaps in preparation for a night out in the metaverse.

The Future of Your Digital Space, Sasha Belitskaja, 2021

The Future of Your Digital Space is a grid of fantastic machines, each with its own whimsical locomotion. While we are used to machines engaging in more utilitarian work, the artist’s contraptions appear to feverishly dance or exercise. They recall the absurd devices conceived of by early twentieth-century artists like Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, only these mechanisms are better suited for the metaverse than the machine age. With a background in architecture and 3D, Belitskaja brings a unique perspective to the exhibition. Rather than modeling her ecosystems from scratch, she cleverly disassembles the bots from her companion piece In Search of Your Digital Self and reassembles the parts as bot-specific imagined environments.

Sofia Crespo

Sofia Crespo is an artist with a huge interest in biology-inspired technologies. One of her main focuses is the way organic life uses artificial mechanisms to simulate itself and evolve, this implying the idea that technologies are a biased product of the organic life that created them and not a completely separated object.

Crespo looks at the similarities between techniques of AI image formation and the way that humans express themselves creatively and cognitively recognize their world. Her work brings into question the potential of AI in artistic practice and its ability to reshape our understanding of creativity.

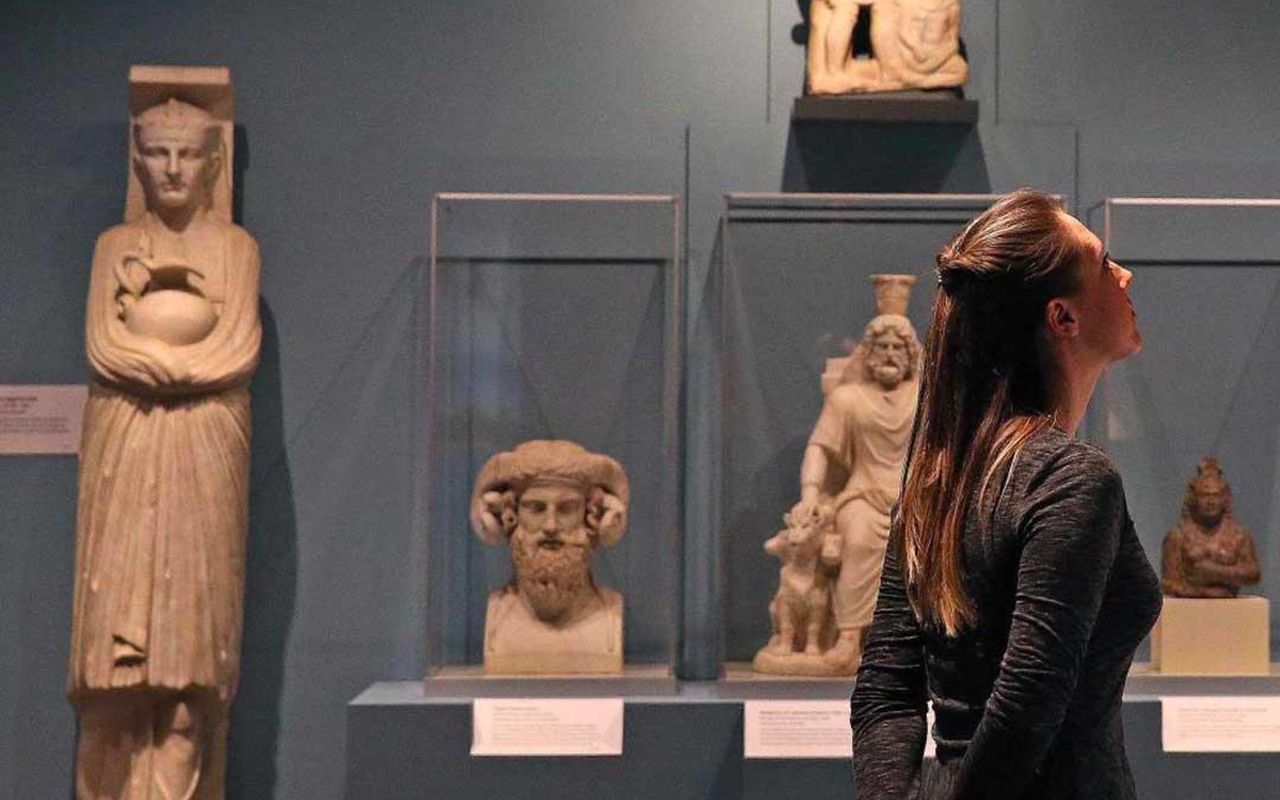

When I initially came up with the idea for a show built around field guides to imagined specimens and ecosystems, Sofia Crespo was the first artist I had in mind. Her description of her own process as “creating new experiences with the familiar” could just as easily have been the subtitle for this exhibition.

neural swarm, Sofia Crespo, 2021

In contrast to the other works in the exhibition, neural swarm is arranged in less of a gridlike formation and more of a clustering that recalls the display of insects at a natural history museum. It is only upon close examination and through additional context that we even realize these bee-like insects are of the artist’s own design, and that they don’t in fact exist in the natural world. As Crespo puts it, “These specimens are part of a collection from a particular neural expedition, a swarm of relatives in all their shapes and life stages.” At first glance, her world appears to be our world. It pulls from colors, patterns, and shapes that are deeply familiar to our conscious and subconscious and plays them back to us in forms that seem fathomable, yet fantastic. The end result is a surreal illustration of an imagined lifecycle for an exquisite species that never existed.

hedgerow still life, Sofia Crespo, 2021

hedgerow still life presents us with an uncanny valley of botanicals. The forms are beautiful, floral, and delicate in nature. They leverage a visual language we think we all speak, but the specifics of the vocabulary are of Crespo’s own device. The closer you look, the less familiar they become, dissolving into something new. It’s like when you have a vivid dream and you are back in your childhood home only to have someone else’s parents walk around the corner. The artist uses neural networks trained on large data sets of images from nature to extract textures, reimagining and remixing our reality into fantastic new worlds.

Jared S Tarbell

Jared S Tarbell is a generative artist who writes computer programs to build software machines. The machines generate geometric structures. Most machines output an infinite number of forms. The forms are expressed as graphic images, machine-cut physical artifacts, video animations, and interactive experiences. Jared graduated from New Mexico State University in 2000 with a degree in computer science. He was the founder of Levitated.net. In an effort to create a better way to sell his digital art online, he co-founded Etsy in 2005 where he was known as the “wizard in the desert.”

My passion for digital art, specifically generative art, started in the early 2000s when I stumbled upon the work of Tarbell. Until that point, I was an analog art bigot with no interest in what I saw as the inhuman and artificial art of machines. Tarbell’s work changed all that. I immediately fell in love with his work the way I love the trees in a forest or the waves in an ocean.

Demo Video - “Entity,” Jared S Tarbell, 2021

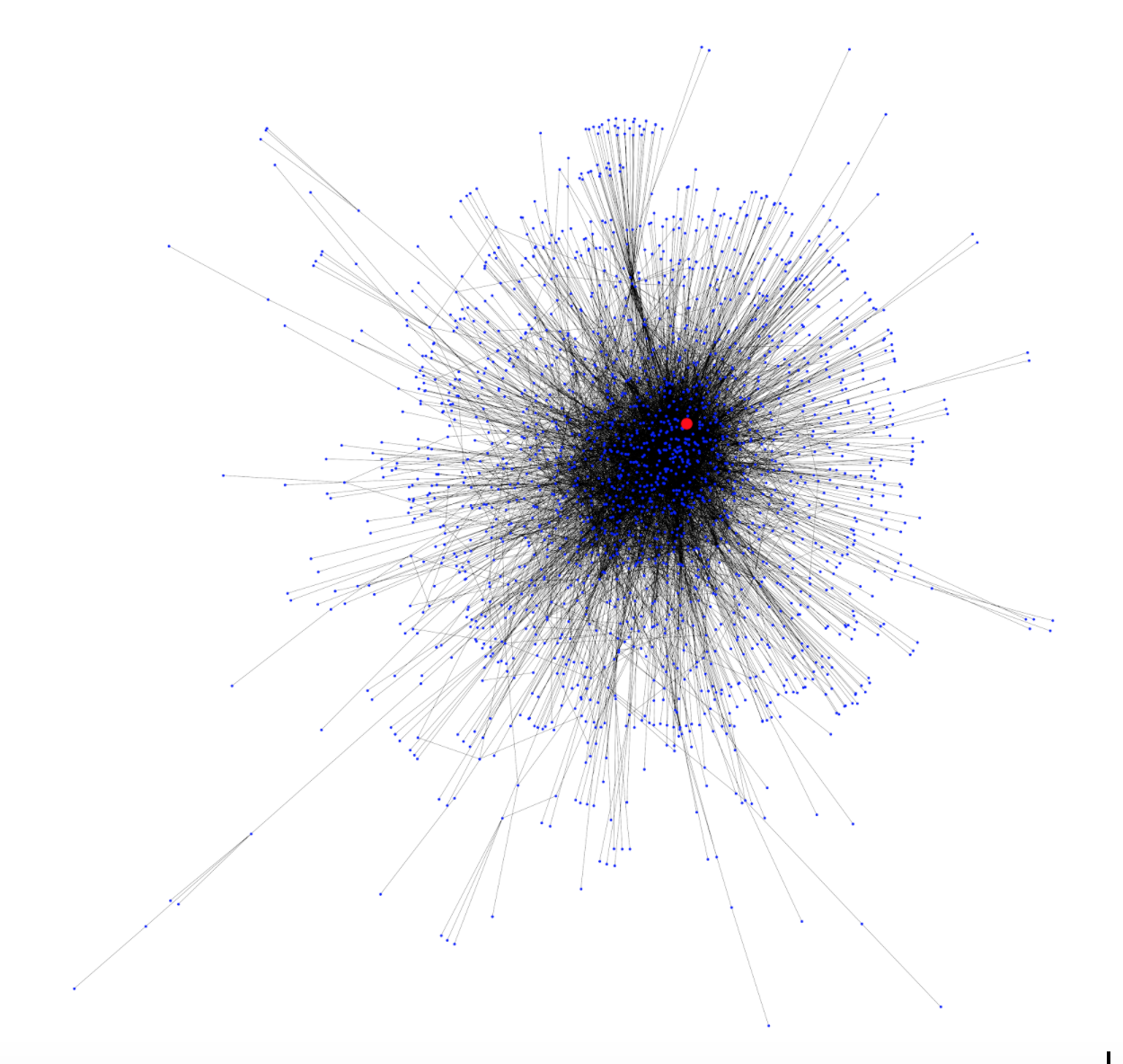

Entity is a wonderful dance of life. Colorful microorganisms are born, engage in naturalistic individual and group behaviors, evolve, and then terminate, making room for new specimens to emerge. The balletic choreography is governed not by linear animation, but through the artist’s deep exploration and understanding of force-repulsion fields. Indeed, work with this complexity and nuance would seem impossible to animate by hand and feels closer to systems and behaviors that we are accustomed to seeing only in nature. Such is the unique brilliance of Jared S Tarbell that his work does not capture nature, it rivals it.

This work is a programmed system and the video artifact was a capture of live interaction by the artist. The collectors will receive the interactive software as part of the acquisition. The music in this piece is Infinity Machine by Tonepoet.

Demo Video - “Environment,” Jared S Tarbell, 2021

Environment is a series of 13 short performances in small multiples capturing the interplay between the artist and his system. We enter the work through a static surface encrusted with primordial barnacle-like corpuscles. The building blocks slowly come to life as the camera pans back, revealing alternative ecosystems. Particles coalesce and disperse under the influence of masterfully programmed forces. According to Tarbell, variations of the system were created in Processing “through an assortment of bitmap assets to represent the nodes and modifications to the flux and warp of the noise field.” The result is a series of stunning environments that range from effervescent and oceanic to celestial and cosmic in feeling. The work is sublime and poetic, and it reflects a lifetime spent mastering computer science and reflecting on nature by emulating its majesty through systems of the artist’s own design.

This work is a programmed system and the video artifact was a capture of live interaction by the artist. The collectors will receive the interactive software as part of the acquisition. The music in this piece is Echoing the Love Words I've Heard From Above by Tonepoet & Wings of an Angel.

Closing

The Field Guide exhibition has been a unique experience for me. As a curator, I typically go through large amounts of existing work with the artists to select which works to include. In this case, I curated the artists, but not the art. It was a bit of an act of faith on everyone’s part. Once given the prompt, they then went off to create new work to be included in the show. I tried to select an eclectic group of artists whose styles contrasted while overlapping enough conceptually to provide a unified show. That it all worked out is a testament to the quality of the artists, and I remain incredibly grateful that they were willing to participate.

I’d also like to thank Casey Reas and the rest of the Feral File team. As an early adopter of NFTs, I’ve been in the space for several years now, and had an interest in generative art for several decades. It was always my hope that those two interests would collide in a meaningful way. And now they have, through Feral File, a platform that values curation and serves as a showcase for both well established and emerging talent from the field. Lastly, I hope you enjoy the exhibition as much as I enjoyed working on it and encourage you to continue learning more about the amazing artists who participated.

![Rules - 2020, Kjetil Golid. [H200-V129–D33–A227], [H244–V60–D84–A121], [H61–V225–D209–A161], [H45–V147–D195–A228], [H247–V149–D176–A21] and [H15–V43–D30–A85]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59413d96e6f2e1c6837c7ecd/1602429935549-WQWP9WE223TEDQ9N4BDW/1_lmYIHgSXq-59A71ogmcdKw.png)