We are in the middle of a generational culture war, and the entire art market is about to be turned upside down by an emerging class of collectors looking to reshape the art world in their own image.

As we enter a new decade, my 2020 art market predictions will make the case that the art market will be unrecognizable ten years from now (in 2030). I build this case on three core beliefs that I will outline and argue in this article:

Artist popularity is more important in driving the price of artworks than any qualities intrinsic to the art

Millennials/Gen-Zers are culturally antithetical to Boomers

Boomer wealth will change hands over the next two decades and Millenials/Gen-Zers will use it to invest in diversity in the arts

I've spent the last three months researching the literature on price prediction and valuation for the art market for an article I submitted to an academic journal. I won't re-write that article here, but I will share that I came away believing we are about to see a massive shift in which artists are propped up by the art market. Here's why:

Art Prices are Largely a Popularity Contest

A Mark Rothko forgery that turned out to be by Pei-Shen Qian

In 2004, Domenico De Sole, former CEO of Gucci and current chairman of Sotheby's, paid $8.3M to the Knoedler & Co. gallery for a painting thought to be by Mark Rothko. The work was one of many painted by art forger Pei-Shen Qian and sold through the gallery to unsuspecting collectors. De Sole sued the Knoedler gallery in 2016 for $25M in damages. When asked if the knowledge that the painting was no longer by Mark Rothko changed its value, De Sole exclaimed, "I think so!" adding, "It's worthless."

Nothing physically changed about the painting — it had the same appearance and the same craftsmanship and quality. Yet it went from being worth millions of dollars to worthless when discovered to be by Pei-Shen Qian instead of Mark Rothko. This extreme devaluation of works discovered to be forgeries happens all the time. Why? Because the popularity of an artist is more important than any qualities having to do with the artwork itself in establishing its price. Mark Rothko is more popular than Pei-Shen Qian, so his work is more expensive.

We’d like to think an artist’s popularity and success is tied to their talent and skill. History shows that gender, skin color, and according to one recent study, where you were born and the level of access you have to a handful of prestigious institutions, are the most important factors in developing a successful career as an artist. Talent-wise, you might be the next Mark Rothko, but if you are not popular with the right group of people, you might as well be Pei-Shen Qian.

This dependency on artist popularity means art prices are especially vulnerable to changes in values from one generation to the next. Millennials and Gen-Zers value systems are measurably at odds with Boomers and we should anticipate unprecedented market upheaval in the coming decades.

Millenials/Gen-Zers are Culturally Antithetical to Boomers

Climate activist Greta Thunberg staring down Donald Trump

If 7-Up is the Uncola, it might be helpful to think of Millenials/Gen-Zers as the "Unboomer." They broadly define themselves in opposition to the ideals of the Boomer generation. They've even popularized the catch phrase "OK Boomer" to efficiently dismiss a generation whose values they see as closed-minded and incompatible with their own. Likewise, Boomers frequently refer to Millennials/Gen-Zers as the "Snowflake Generation" for believing that they are each unique and special, seeking too much attention, and being over-emotional and sensitive.

How big is the gap in values between generations, and where do they differ? Polls show children and grandchildren of Boomers are far more tolerant on critical issues like diversity and gender norms. They are also much more concerned about the climate crisis.

68% of Millennials prefer movies and TV shows with diverse casts vs. 32% of Boomers

70% of Millennials support gay and lesbian marriage vs. 39% of Boomers

56% of Millennials see a link between human activity and climate change vs. 45% of Boomers

How do these polls play out in real-life decision making? No generation is monolithic, but you can tell a lot about a group's values by who they elect as their leader and which artists benefit most from their patronage.

In 2016, more than half of the Boomers who voted in the United States voted for Donald Trump as their president. Trump's best-known mantras are "your fired" and "build a wall." Both are messages of exclusivity and subjugation designed to bully and humiliate those in less powerful positions. Trump's persona is a caricature of the 1980s playboy built on public displays of extravagance and wealth. His attitudes towards women inspired the largest single-day protest march in US history just one day after his inauguration. Trump's administration has not been friendly to LGBTQ rights. And finally, Trump is anti-science and does not agree with experts about climate change, calling it a Chinese hoax.

Obviously, Trump embodies some firmly held Boomer ideas about leadership, or else the majority of them wouldn't have elected him as their president. But is Trump an anomaly or a true reflection of Boomer values? Let's follow the money and look at which artists most benefited from Boomer patronage to see if there's a trend.

Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst have generally ranked near the top of the list for being the wealthiest living artists over the last several decades. Like Trump, both are white, male, and rich. They both made hundreds of millions of dollars by outsourcing the art-making process to craftspeople and then laid off most of those people in many cases with little cause or notice. Like Trump, both have built their personas around conspicuous consumption and ostentation.

Damien Hirst - For the Love of God, 2007

Hirst, who has said money is important as love and death, is known for creating a diamond-encrusted skull that fetched $100M in a private sale in 2007. Koons’ stainless steel sculpture of a cheap inflatable rabbit sold for $91M last year, setting a new auction record for a living artist.

As with Trump, Koons and Hirst have mastered the art of using shock tactics to keep their names in the press and to stay visible and relevant. Koons by hiring adult film star Ilona Staller to have sex with him for a pornography shoot and then selling photo-realistic paintings and tacky sculptures of the sex acts as his art.

Jeff Koons, Dirty – Jeff On Top, 1991.

Hirst kept his name in the news by killing animals, cutting them in half, and floating them in large tanks of formaldehyde. In 2017, Artnet estimated nearly a million (913,450) animals had given their lives for Hirst's art.

Damien Hirst, The Prodigal Son, 1994

In the notoriously illiquid art market, it often takes a generation before an artwork is resold. Will Millenials and Gen-Zers who grew up in the #metoo movement and losing sleep over climate change be interested in the artists that were propped up by Boomer wealth?

Millennials/Gen-Zers Will Shape the Art Market in Their Own Image

In the next 25 years an estimated forty-five million US households will pass down an unprecedented $68 trillion to their children and grandchildren, according to a report from Cerulli Associates.

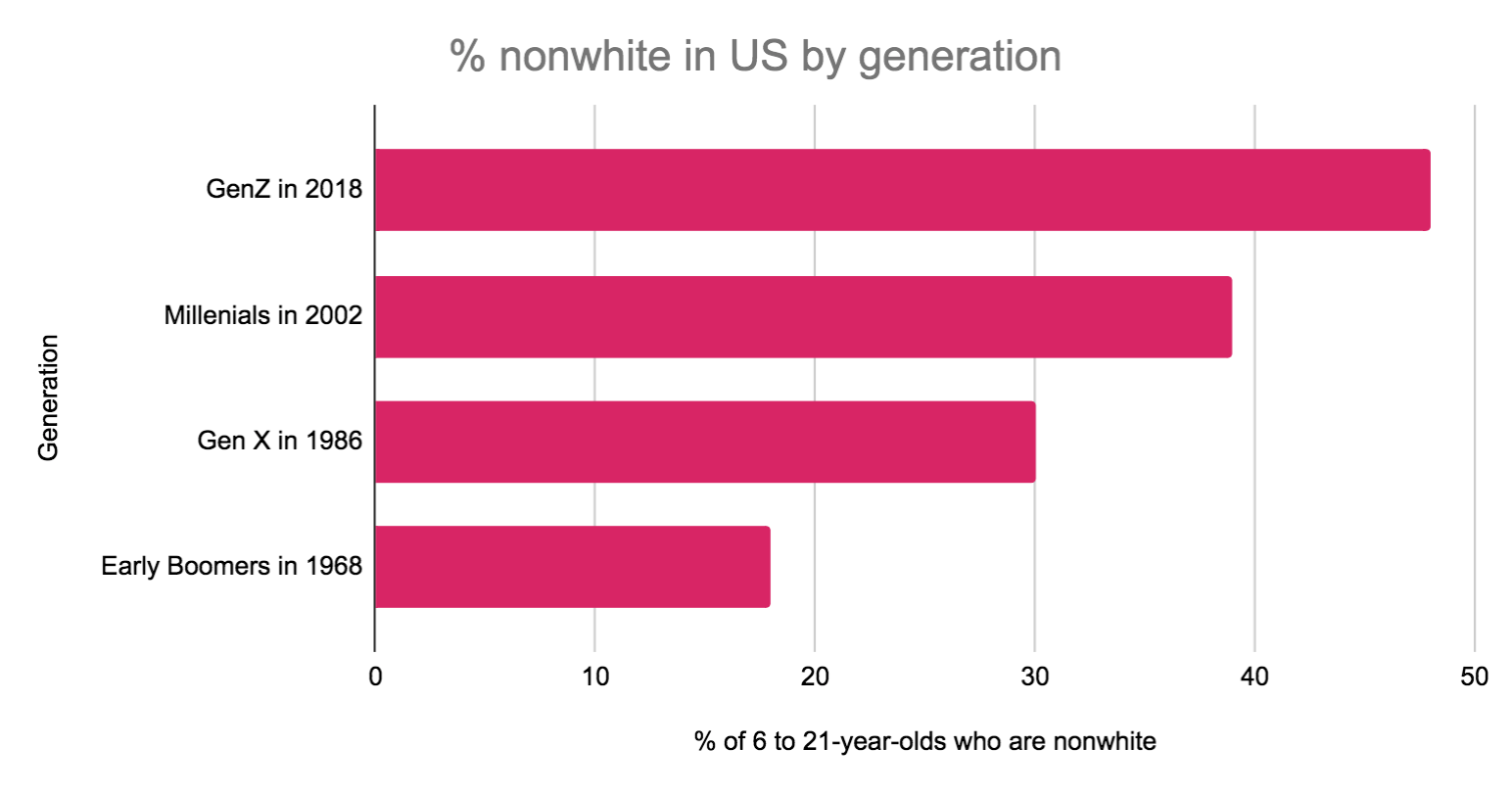

With this wealth transfer will come a new generation of freshly minted collectors eager to build an art market in their image. As the most diverse generation in the history of the United States, we should anticipate a greater variety in the gender and race of the artists who will benefit at the highest levels from their patronage. We should also expect that this younger generation of collectors will be much more concerned about climate change and ecological instability. And lastly, Millenials/Gen-Zers are already far more likely than Boomers to buy online. 93% of high net worth Millennials had purchased art online vs. less than half of high net worth Boomers, according to a 2019 UBS report.

We are already seeing some progress for diversity in the art market. In the last six years, art by women increased in value by 72.9% vs. 8% for art by male artists as tracked by Sotheby's Mei Moses index. But as the stats below indicate, we are nowhere near parity.

Only 2% of auction sales between 2008 and 2018 were by women

Just 11% of all work acquired by US museums in the last decade was by women

Just 14% of museum exhibitions in US featured female artists

The art world's track record for supporting artists of color is equally poor. Again, the stats show we are nowhere near parity:

Just 2.3% of all acquisitions by museums were of art by African-American artists from 2008 - 2018

Just 1.2% of art in American museums is by African-Americans

Museums are racing to atone for past discretions, and many are literally de-accessioning paintings by well-known white male artists to fund the acquisition of works by women and artists of color. We should expect similar corrections to private collections and in the art market.

Which Artists Will Benefit Most From a Generation Eager to Highlight Diversity?

Jean Michel Basquiat - Untitled, 1982

The $63.7B-a-year art market is notoriously top heavy, with just 1% of artists accounting for 64% of sales value. And the vast majority of that 1% have two things in common: They are white and they are male. This should change in the next two decades.

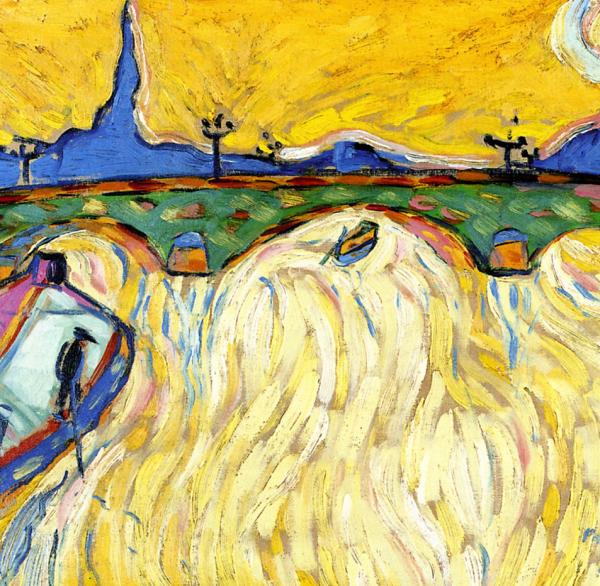

Expect several female artists and artists of color to break into the highest echelon of the market, joining the likes of Van Gogh, Monet, Picasso, Rothko, Warhol, etc. We have already seen Jean Michel Basquiat break through the ceiling with his Untitled, selling for $110M in 2017. I believe artist Alma Woodsey Thomas also has a good shot at breaking into the 1% Club.

Alma Thomas at the opening for her show at the Whitney

Thomas is an incredibly strong painter. Find a museum showing her work and see for yourself how her paintings hold up against all the other ab-ex and color-field titans of the 20th century. From a talent perspective, Thomas is clearly one of the most important colorists of all time, but we know talent is only part of the story — and not even the largest part.

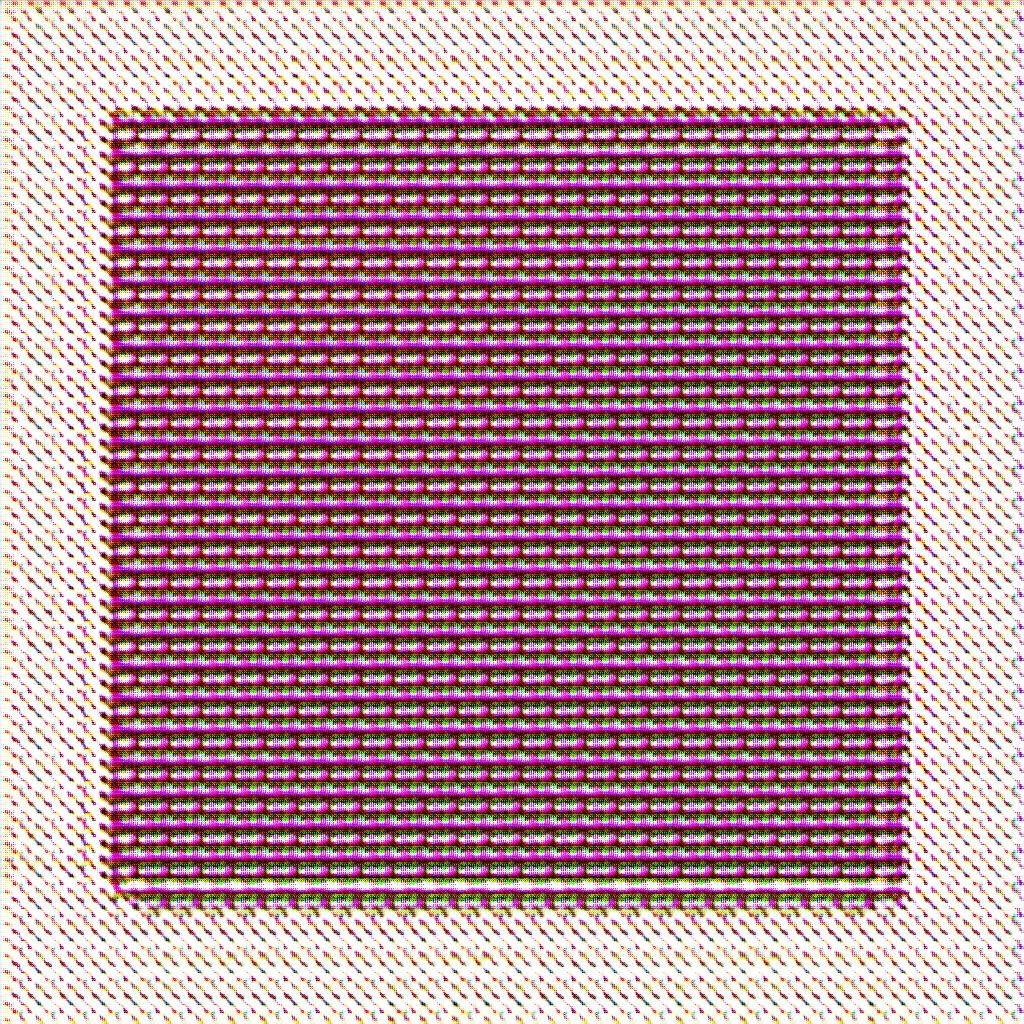

Alma Thomas, A Fantastic Sunset, 1970

Since we know the price of art often has more to do with popularity of the artist than the quality of the artwork, it is essential to look at Thomas' bona fides, which are nothing short of remarkable — especially given the all of the discrimination she faced.

First African- American women to graduate with an art degree

Earned a Master of Arts degree from Columbia University in 1934

First African- American woman to receive a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum (1974)

Resounding reviews in The New York Times in an era of prejudice and bias

Selected by the Obamas for display in the dining room of the White House

Alma Thomas’ Ressurection hanging in the White House dining room.

Thomas' market is already a rocketship. In 2017, a new record was set for her work with the sale of Spring Flowers for $387,500. That record fell again in 2019 when A Fantastic Sunset sold for $2,655,000. The ceiling on her work effectively increased 580% in just two years, and there is still plenty of room to grow. We’ve known that Thomas is among our greatest painters for a very long time. We just needed to wait for a generation excited to embrace and celebrate artists of all colors and genders to come along before we could give her the proper recognition she deserves.

Not all the artists whose success was limited due to discrimination will break into the 1% Club. But we will see the fingerprints of Millennials/Gen-Zers correcting for centuries of bias across all levels, not just the top of the market. For example, important works by Agnes Denes and Vera Molnar, pioneers in environmental art and generative art, respectively, can still be collected for under $10K. I expect the market for both these category-defining artists to heat up quite a bit over the next ten to twenty years.

Denes, who currently has a retrospective at The Shed in NYC, is positioned to break out into the mainstream and establish her legacy as the leading figure in environmental and ecological art.

Agnes Denes, Wheatfield—A Confrontation, 1982

Denes is best known for her work Wheatfield—A Confrontation, which featured two acres of wheat planted and harvested by the artist on the Battery Park landfill in Manhattan during the Summer of 1982. Denes explains that Wheatfield "referred to mismanagement, waste, world hunger, and ecological concerns. It called attention to our misplaced priorities." Wheatfield, with its dual focus on the environment and economic inequality, fits perfectly into the post-Boomer zeitgeist.

Among Denes’ many significant accomplishments:

The grand scale and conceptual nature of Denes’ works does make them challenging to collect. However, she also created many “philosophical drawings” and prints, exploring isometric systems and complex map projections. These drawings can be found in the MoMA and other important collections and periodically come up at auction for very reasonable prices.

Agnes Denes, Map projection: the snail, 1976

Denes' work and views on the environment will only feel more prescient and relevant as time moves on. As the next generation of collectors scour history to find artists who gave us early warnings that we needed to take better care of our planet and the people who inhabit it, Denes' name will regularly show up at the top of the list of those few who did.

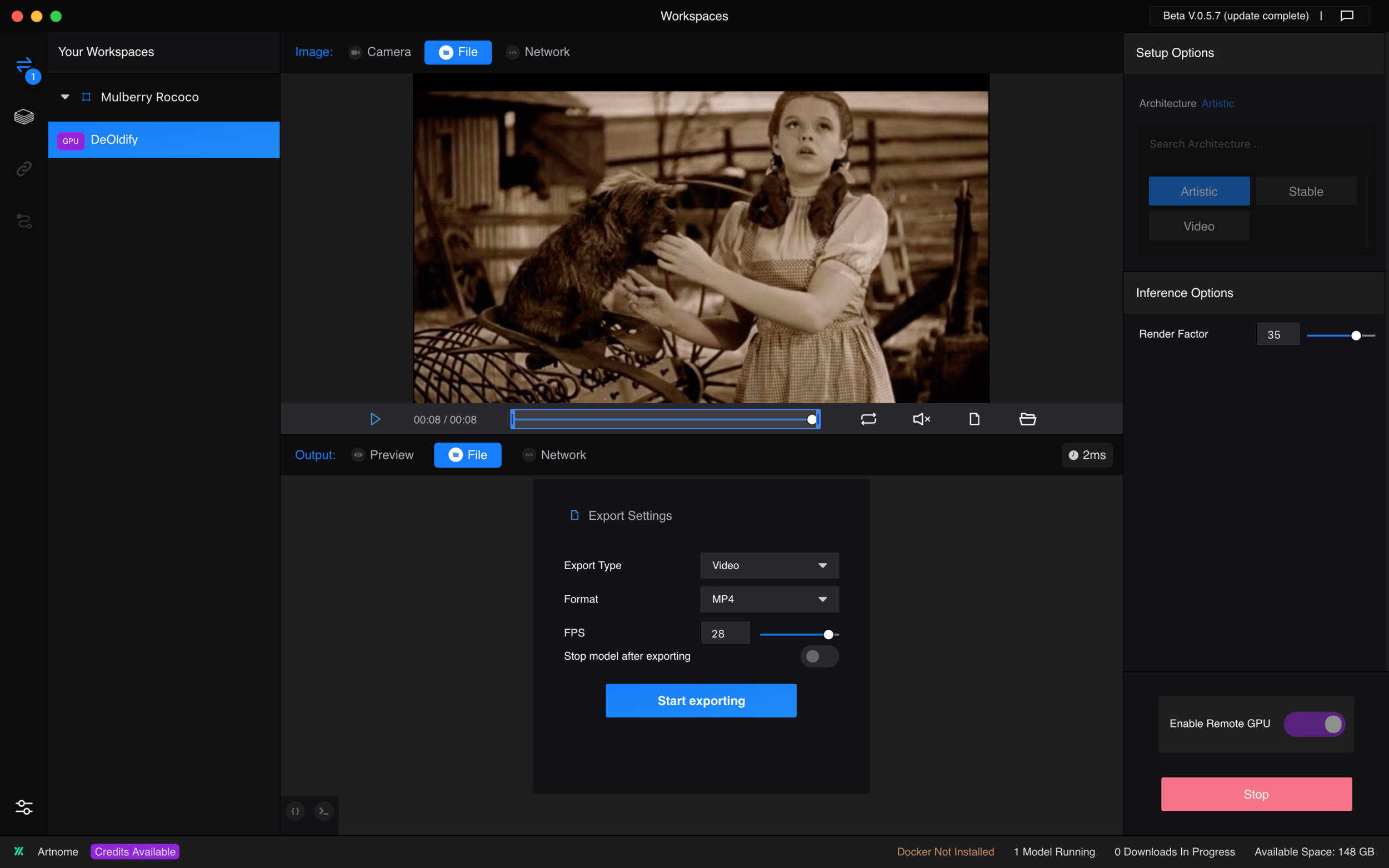

In addition to their concerns over climate change, Millenials/Gen-Zers are also the most technologically fluent generation we have seen. Given their interest and comfort with tech, I believe that the market for generative art — art generally created in code using autonomous, automated systems -- will explode in the next two decades. As one of the only early generative art pioneers to come to computers in the 1960s with decades of experience as a working artist, I believe Vera Molnar is perhaps the most important generative artist of all time.

Vera Molnar

At the age of 96, Vera Molnar has now created cutting-edge art that explore algorithms with and without computers across eight decades. Molnar helped bridge the gap between computers, which were thought to be cold and antagonistic to human creativity, and traditional artistic practice. She once said that “ultimately the intuition of an artist is the ‘random walk’ of the computer.” Her work paved the way for a generation of influential generative artists and will continue to indefinitely into the future.

Even the art world, slow to embrace women and slower to embrace tech, is finally starting to take notice of Molnar’s work and achievements:

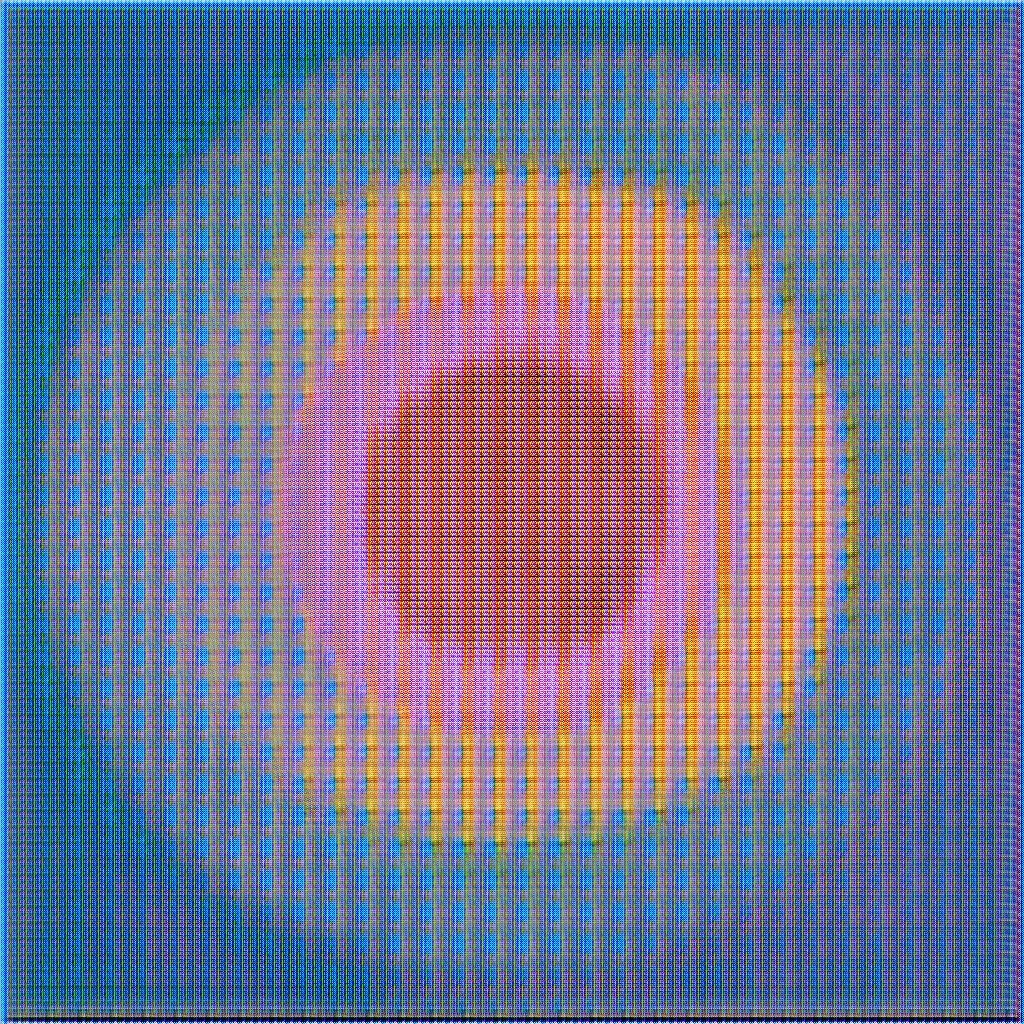

Vera Molnar - (Dés)Ordres, 1974

If I had tens of thousands of dollars to spend on art, all of it would be going to build a collection of important works by Vera Molnar. However, my meager art budget requires that I look for work that costs a few hundred dollars at most, not tens of millions or even tens of thousands. In many ways, I prefer this. I see collecting as an act that can be just as creative as making art or curating an exhibition. If I were spending tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars, I’d be thinking in terms of a financial investment instead of just looking for art I truly love by artists I want to support and see succeed.

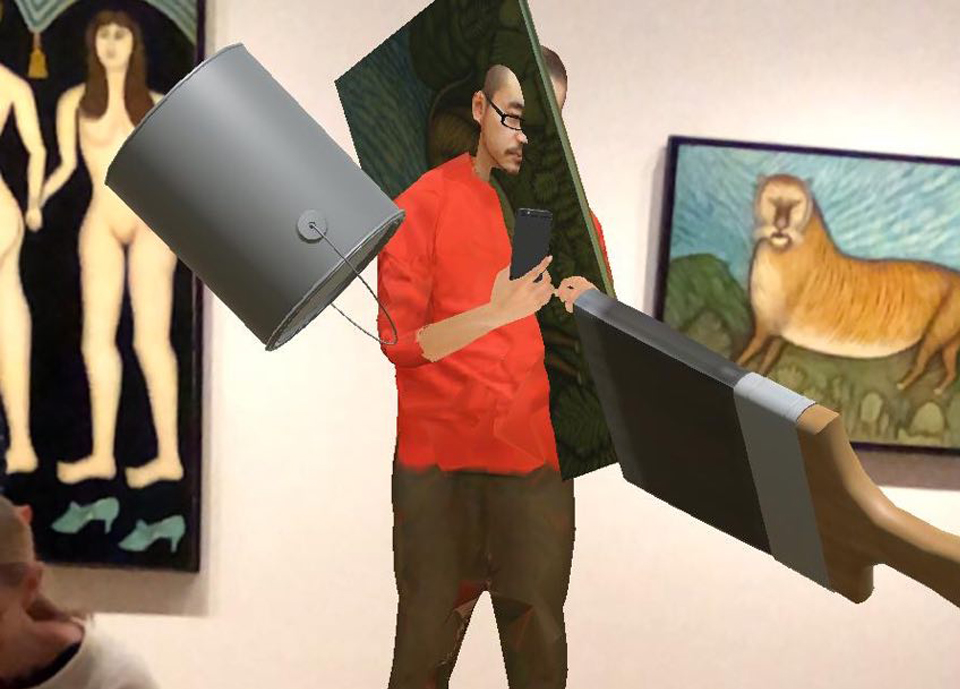

Osinachi - Can’t Sleep, 2019

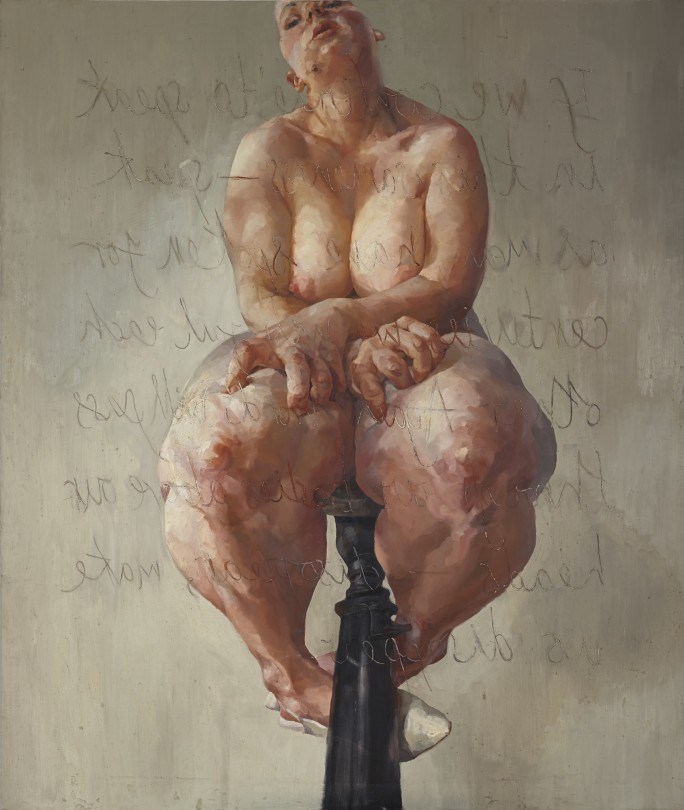

Lately I have been buying as much work by artist Prince Jacon Osinachi Igwe as I can get my hands on. For me, Osinachi reflects the best of what the coming generation of artists have to offer.

Osinachi’s work stands out in part because he is self-taught and creates his work using Microsoft Word, a common word processing tool few would ever think to use for making art. His signature use of color and pattern create sophisticated compositions that are dynamic, but flat like a collage, unusual for artists working digitally. His work is bold, distinct, authentic, sincere, and addresses his generation’s desire for equality, diversity, and environmentalism in a way that is direct without being too on the nose.

Osinachi signing a print of Nduka's Wedding Day, 2019

Osinachi is an intellectual. His writing is as thoughtful and candid as his art. His 2015 story A Man and His Breasts is a sensitive portrayal of a boy growing up in Nigeria with gynecomastia. It gets to the same core elements present in his visual art — the pain and suffering all of us feel at times for simply living and being who we are in a world full of rules and systems designed to make us feel shame and fear. Or, as Osinachi describes it, “visible existence as protest.”

Osinachi lives and works in Nigeria, a country which has some of the most brutal anti-LGBTQ laws in the world. By law, members of the LGBTQ community can be whipped or face up to 14 years in jail for showing public affection to same-sex partners. The laws have become so strict that simply being accused of having a “gay” hairstyle or clothing can get you arrested.

Osinachi - Nduka's Wedding Day, 2019

In this environment, Osinachi bravely celebrates people from the LGBTQ community in his work, showing them as everyday people flourishing in their lives. This can be seen in his wonderful work Becoming Sochukwuma, inspired by a 2014 essay I Will Call Him Sochukwuma: Nigeria’s Anti-Gay Problem, written by Chimamanda Adichie in reaction to Nigeria's anti-gay law. It can also be seen in the celebratory Nduka's Wedding Day featuring a male bride on his wedding day holding a bouquet.

Prince Osinachi - Becoming Sochukwuma, 2019

Osinachi’s work covers many other topics challenging stereotypes around single motherhood, highlighting the need for diversity, and protecting the environment. And some of his work is just plain fun.

Osinachi - NWANYỊ AHỤ NA-AKWA AKWA, 2019

In a world where artists resort to making porn or sawing animals in half to get attention, Osinachi is bravely fighting for people to be able to live as they are. It’s a welcome use of art and its potential to positively impact society.

Measurable Predictions for 2030

OK, not going to let myself finish without making some bold and measurable art market predictions for you to hold me accountable for. Based on the extreme shift in values and the ensuing wealth transfer, I predict that by 2030:

Works by five non-white and or non-male artists will sell for more than $50M each

Women move from 2% of sales at auction to at least 10%

Women shift from 11% of all work acquired for permanent collections to at least 25%

Women will go from being featured in just 14% of exhibitions to 30%

Acquisitions of art by African-Americans by major US museums will go from 2.3% to 10%

Art in US museums will go from 2.5% by Latino Artists to 5%

In summary, art’s price is built around popularity. What was popular with the Boomers is mostly unpopular with Millenials and Gen-Zers. Specifically, these younger generations are more interested in diversity, more concerned with climate change, and more comfortable with technology. We should expect that artists propped up by Boomer wealth may have a hard time finding buyers in ten or twenty years — specifically, artists who sexualized or objectified women or treated animals or the environment poorly. By contrast, many talented female artists and artists of color will see their work increase in value -- not because of their gender or skin color, but because they have always been great and only needed a more open-minded generation to be fully recognized for their talents.