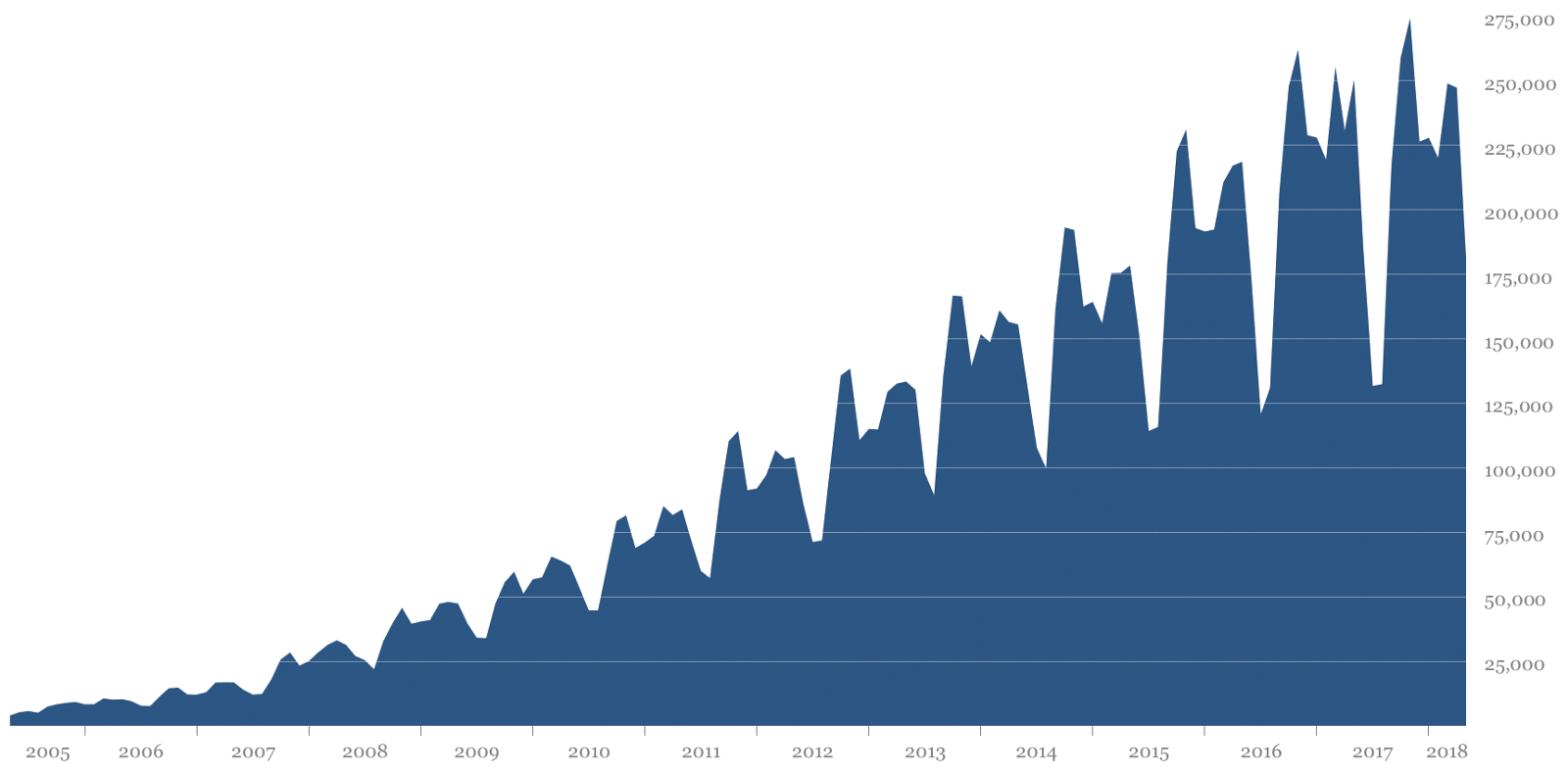

I wrote my first article on blockchain and art almost a year ago. Bitcoin has plummeted by 64% and Ethereum by 86% over that same period. Once thought to be a promising new way to fund new ideas and startups, ICOs (initial coin offerings) are now viewed with extreme skepticism, and all but disappearing.

From an outsider’s perspective, one could easily assume in this climate that the blockchain use case for art would be dead. But from the insider’s perspective, nothing could be further from the truth.

As the “get rich quick” ICOs and cryptocurrency speculation of late 2017 has subsided, the potential for blockchain to solve real-world use cases for art has only grown. Even I have been surprised by how resilient and fast moving things are in the blockchain art space during this span of cryptoCurrency free fall.

In this post, we talk directly with the key innovators in the space and look at some of the strongest signs of momentum in the adoption of blockchain for the world of art, including:

Christie’s auction house partnering with startup Artory to roll out a blockchain pilot for the auction of the Barney A. Ebsworth Collection, estimated to exceed $300 million.

Established artists like Ai Wei Wei and Eve Sussman exploring the blockchain and CryptoArt.

Ambitious startups creating innovative tools and services making it easier for artists of all abilities to take advantage of the blockchain.

While we have seen fewer headlines on blockchain and art in the last few months, it has also been the most productive time period for the space. I’m not sure if there is causation here, but I’m certainly not willing to rule it out.

Christie’s to Record Sales on Blockchain

Horn and Feather, Georiga O’Keefe, oil on canvas, 1937

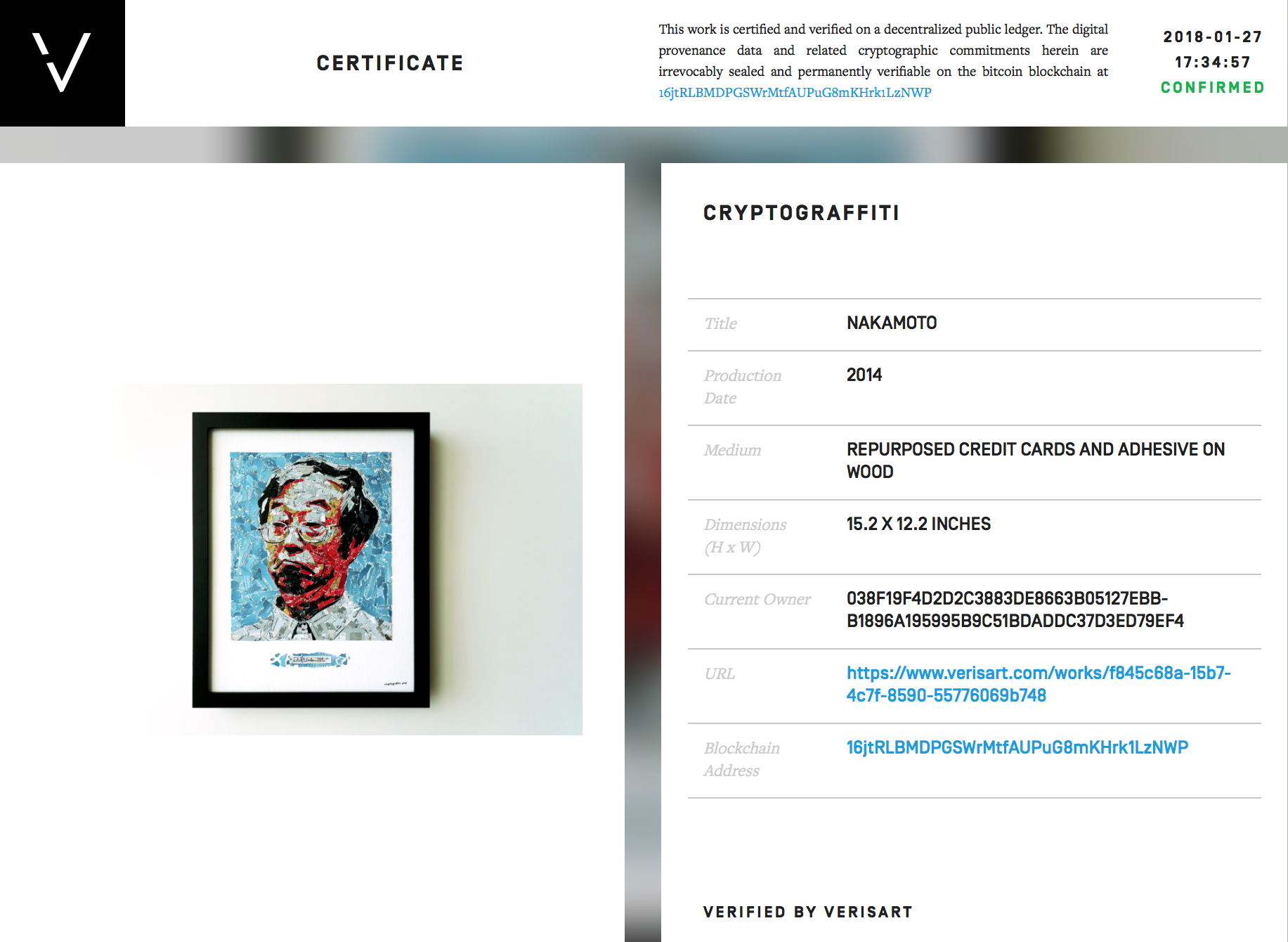

In my last article, “Art World, Meet blockchain,” I implied that large organizations like Christie’s would be better served teaming up with smaller, more nimble startups to explore technological innovations like blockchain. Christie’s has since made the right move in my opinion, forming a partnership with the blockchain title registry Artory.

Artory brings the rapid innovation of a startup, but with a known quantity at the helm in founder Nanne Dekking, who also serves as the current chairman of TEFAF (The European Fine Art Foundation).

Though pitching it as a pilot, I am pleasantly surprised that Christie’s chose the highly visible Barney A. Ebsworth Collection as their foray into blockchain. The Ebsworth Collection is widely recognized as the most important privately held collection of twentieth century American art. The collection is estimated to exceed $300 million total at auction and will be entirely recorded on the blockchain.

On a personal note, I am particularly fond of many of the artists who feature in this collection, as Stuart Davis, Arthur Dove, Charles Sheeler, Marsden Hartley and others are well represented in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Woman as Landscape, Willem de Kooning, oil and charcoal on canvas, 1954-1955

I asked Christie’s CIO Richard Entrup how the use of blockchain might impact the Ebsworth auction experience and if we should anticipate further adoption of blockchain from Christie's moving forward. Entrup shared:

Christie’s leadership in global sales is reflected and supported by continued investment in digital platforms and initiatives that work for our clients. Our pilot collaboration with Artory is a first among the major global auction houses, and reflects growing interest within our industry to explore the benefits of secure digital registry via blockchain technology.

We are running this as a pilot and there is no risk or we would not be doing it. Christie’s will retain all information about the buyer. The certificate relates to the object, not the owner. We will consider the future use of blockchain in our business at the end of the project. As ever, any changes will be led by our clients’ needs.

I think this crawl, walk, run approach is the exact right one to mitigate potential concerns from their collector base while exploring the upside that blockchain could bring to their business and the art industry at large. It is clearly a win for Artory and a reflection of the trust Nanne Dekking has established in the art world. I asked Nanne for his thoughts on the partnership:

We are honored that Christie’s is teaming up with our blockchain-secured art registry for its upcoming sale of the Barney A. Ebsworth Collection of American modernism. The house will become the first major auctioneer to apply the innovative technology. For first-time buyers and experienced collectors alike, Artory provides: the reassurance that they are dealing with a vetted seller; that there will be an immutable record of the transaction; and that they will receive a certificate of sale from an independent third party—all of which encourage them to act with confidence.

Artory will create a digital certificate of each transaction for Christie’s, and the latter will provide their clients with a registration card to securely access an encrypted record of information about their purchased artwork on the Artory Registry. Artory not only gives buyers the confidence they crave, it enhances their entire experience. Offering up-to-date information from trusted resources about transactions and the market in general, Artory saves buyers time and money when performing due diligence. Furthermore, unlike current bills of sale, which are easily lost or forged, Artory’s standardized certificates of sale take the headache out of collection management, providing irrefutable proof of ownership without compromising buyers’ anonymity or privacy.

It’s essential for some of the larger institutions like Christie’s to come on board if blockchain registries are going to become mainstream in the art world. I’m rooting for Christie’s blockchain pilot to add real value in the form of better provenance and data transparency and hoping that it serves as a foundation for expansion and not just a one-time experiment.

Blockchain, Artists, and Exhibitions

Kevin Abosch (left) and Ai Wei Wei

While the Christie’s partnership signals interest among collectors for using blockchain to better catalog art, interest in and by artists has also never been greater.

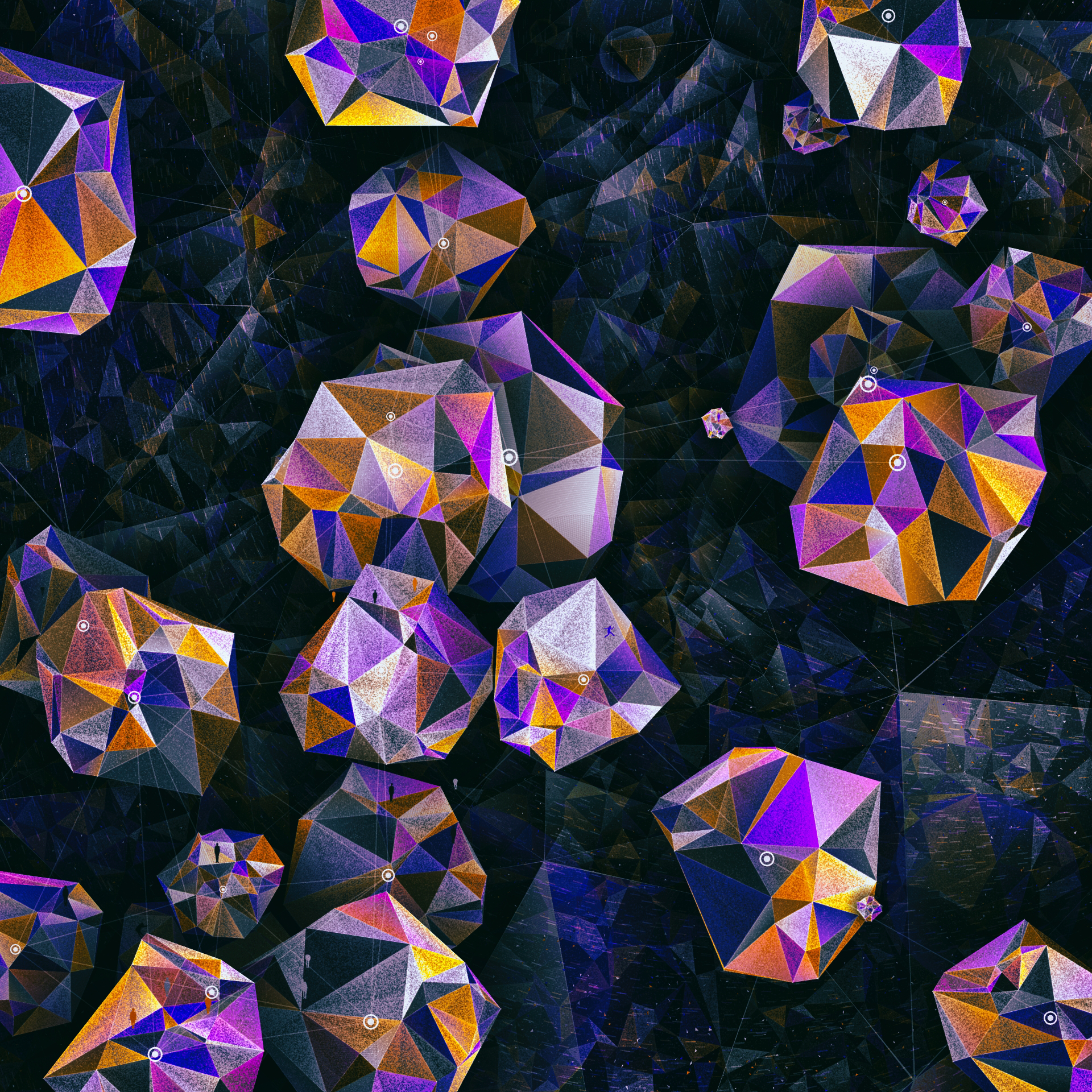

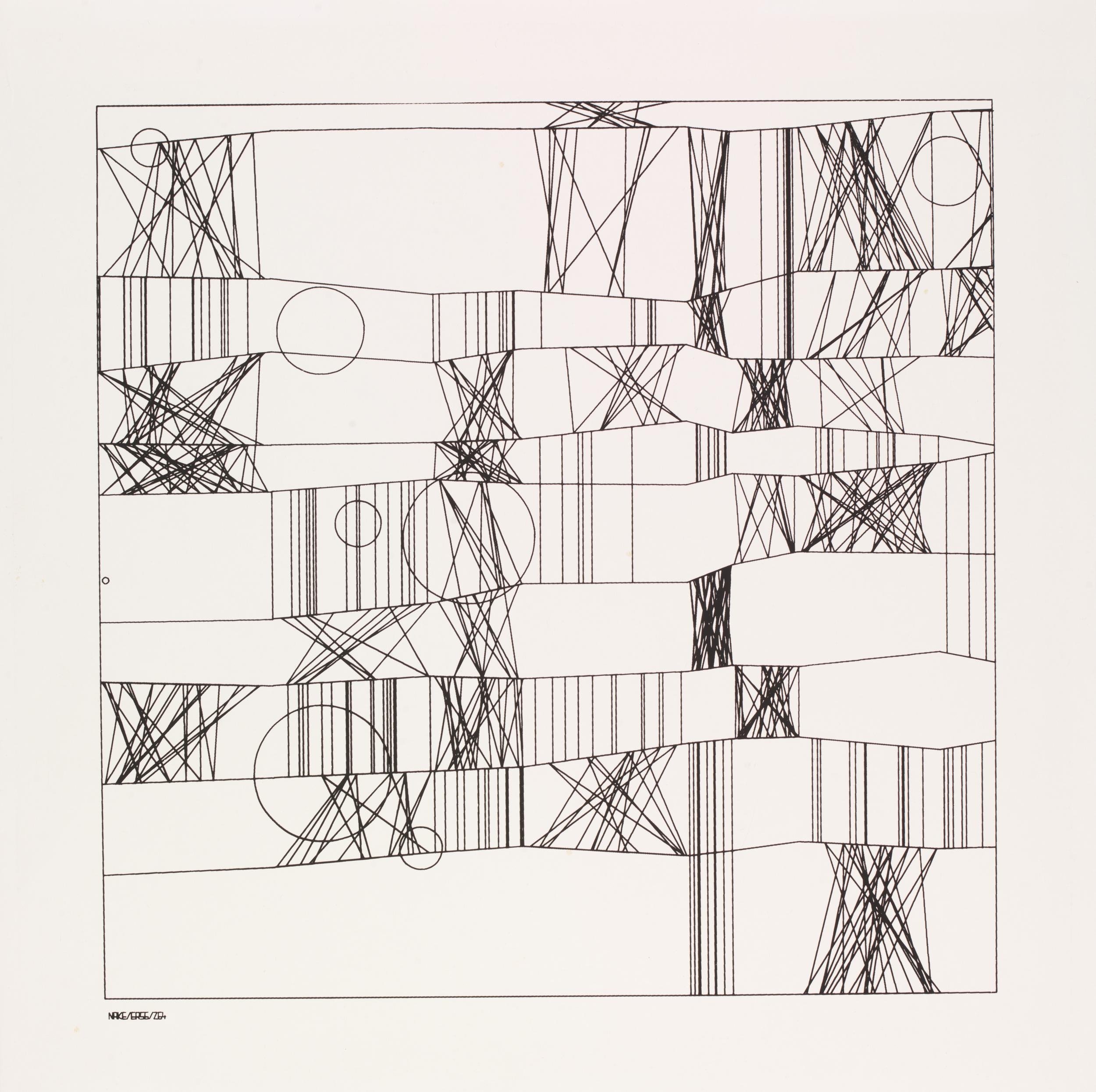

{Perfect & Priceless} Value Systems on the Blockchain, a show at the Kate Vass Galerie in In Zürich , Switzerland, curated by generative art expert Georg Bak, will open on November 15th and run through January 11th, 2019.

The show features many of the most innovative artists working with blockchain today, including collaborators Kevin Abosch and Ai Wei Wei, Matt Hall and John Watkinson of CryptoPunks, and blockchain art pioneer Rob Myers.

While all of the works in the show explore “value systems” as the title implies, I find materiality as a secondary theme to be the most interesting lens through which to view the work. Or as CryptoPunks artist John Watkinson puts it, “Bridging the divide between the digital and the physical.”

One of my favorite works in the show is the Chaos Machine by the Distributed Gallery, an art collective from France. Side note, if you are an astute and regular reader of Artnome, you may remember the Distributed Gallery as the team behind the controversial Richard Prince token, whose anonymity I exposed, and whom I then interviewed in great depth.

Chaos Machine, The Distributed Gallery, 2018

Chaos Machine, The Distributed Gallery, 2018 (close up)

The Distributed Gallery’s Chaos Machine literally burns fiat (paper currency) and turns it into what they call a “chaos coin.” This is not a physical coin, but rather a blockchain-based cryptographic token. For me, the spectacle of watching the currency burn draws attention to the absurdity of wealth being stored and transmitted through such a seemingly arbitrary and fragile object as a paper bill in an age where all things are rapidly moving towards digitization.

Though there is no direct connection between the burning of the paper currency and the production of the chaos coin, it feels as if a transfer of value has been facilitated by the machine. Our mind establishes a cause and effect relationship based on a sequence in which one symbol of value is destroyed and another is born. The sequence also narrows the gap in the reverence held for established government-backed paper currencies versus the initially absurd-seeming chaos coin. Is a chaos coin really all that different from a banknote? The philosopher Bernard Aspe (as translated by Daniel Shavit) writes about Chaos Machine:

…it is because all the others place their trust in this strange object, the banknote (or the cryptocurrency unit), that I too can trust. I trust the trust of others. It is only in this way, only as trust that refers only to itself, that value «exists»…

…Behind the bill that is consumed, there is nothing - literally, and what is made visible here is above all nothingness…

…The new currency necessarily reproduces, for the most part, the aberrations of the previous one. Its main merit, however, is that it is more open about what is nothing to the principle of social interaction…

For me, Chaos Machine highlights how physical currency feels antiquated, clumsy, and vulnerable (not to mention government-dependent) in an age when music, books, and now art are increasingly moving towards the digital. With Chaos Machine, the Distributed Gallery has compressed the transition of digitalization which is being played out across decades into a single act. Simply insert the bill, watch it burn, and receive your new digital currency. This not only makes the transition to digital currency more visceral, but also makes for good theater.

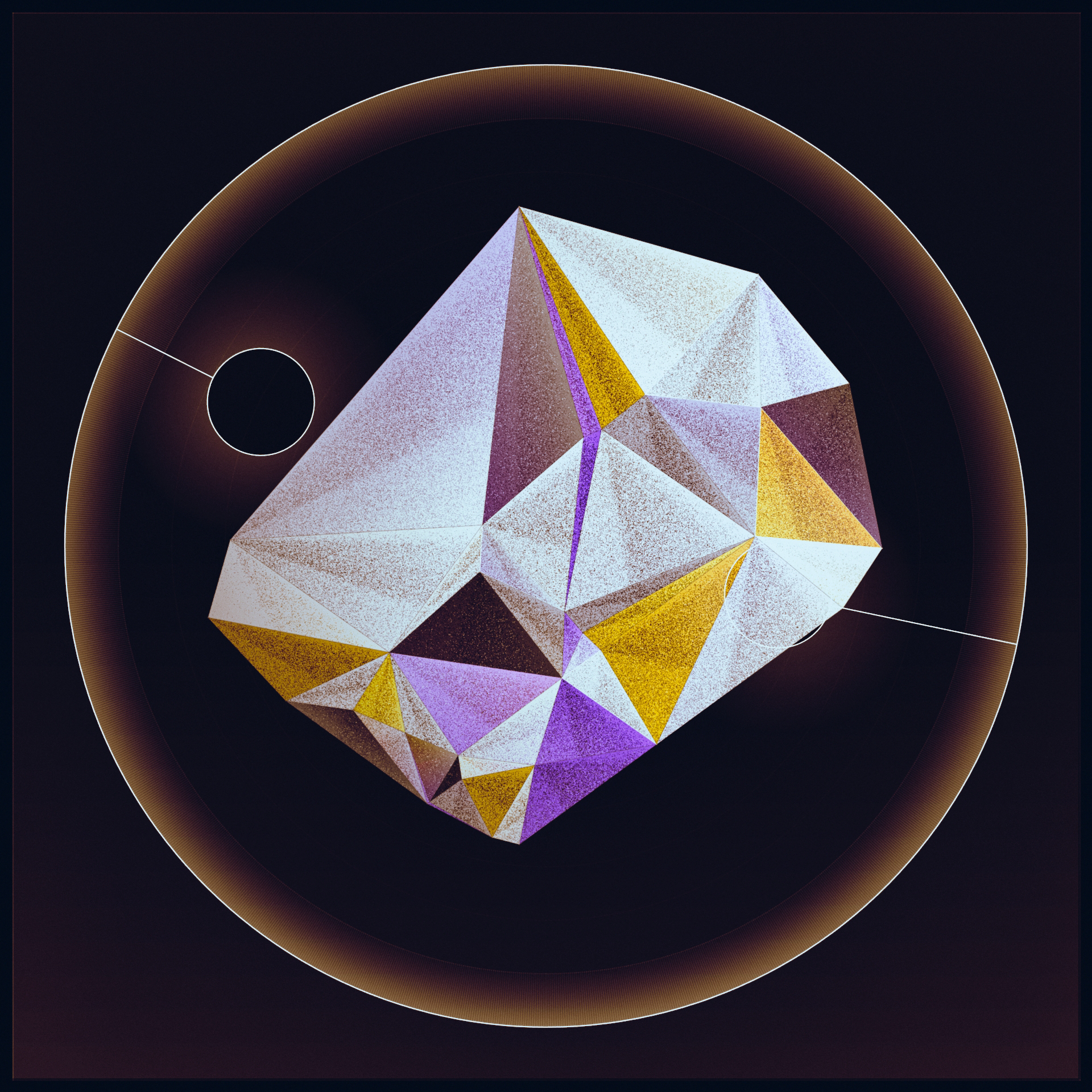

CryptoPunks, printed version with paper wallet and wax seal

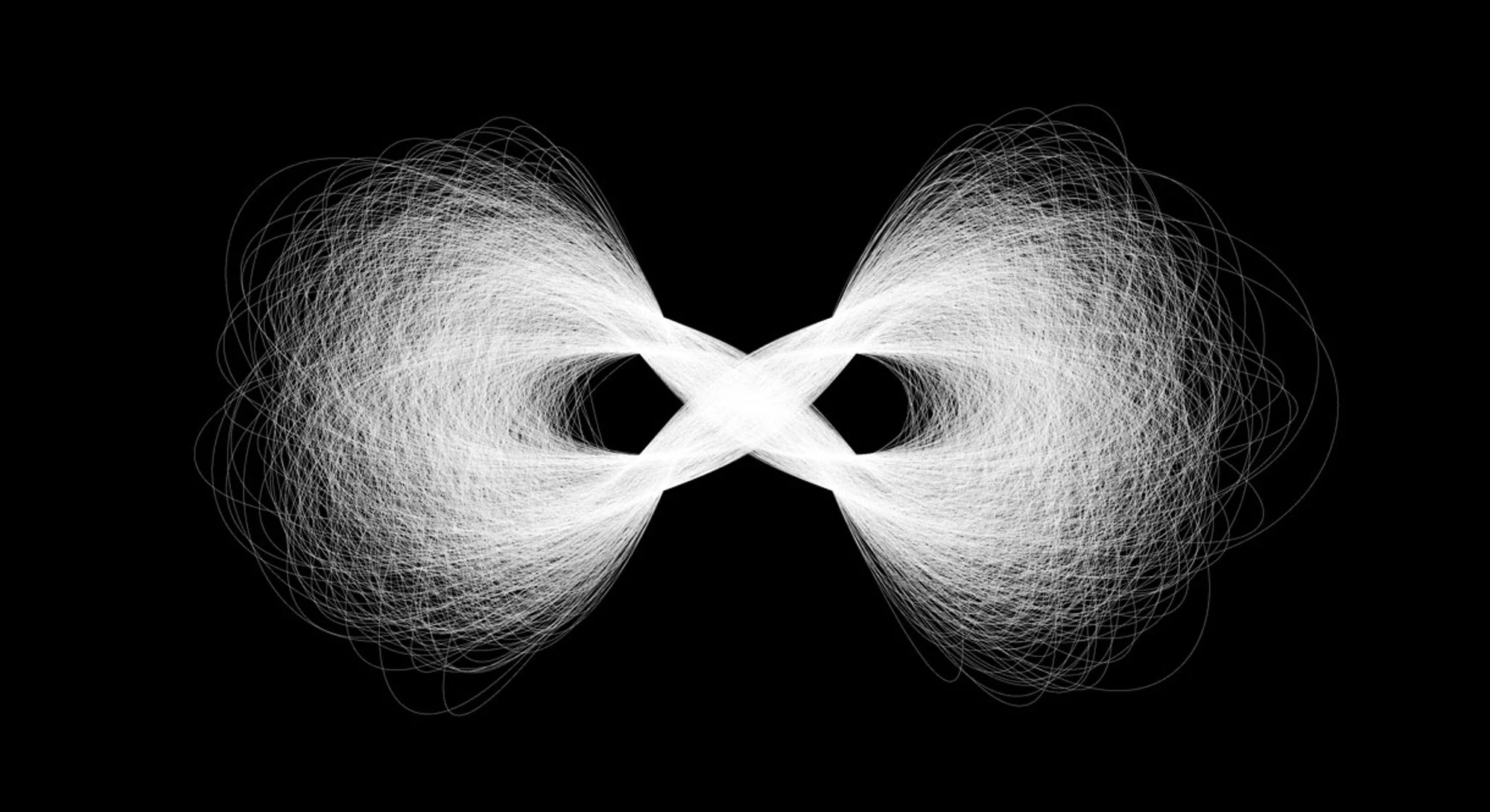

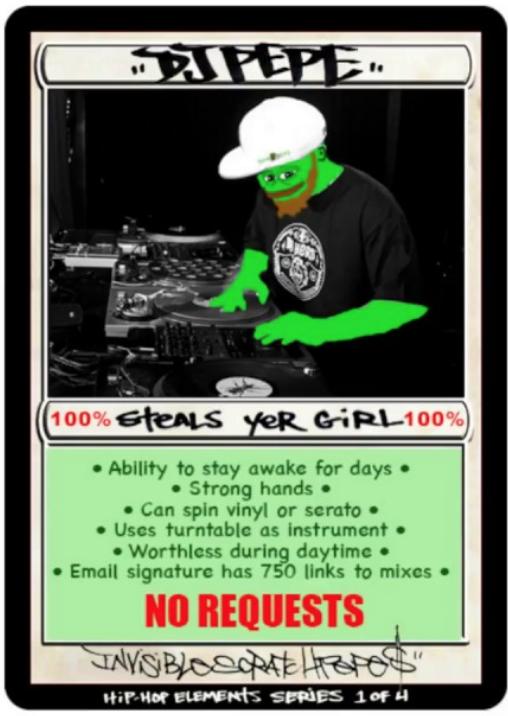

In contrast to Chaos Machine, the work being shown by Matt Hall and John Watkinson of the CryptoPunks runs the process of digitization in reverse. They will present the first ever printed CryptoPunks, displayed in a grid of nine unique artworks.

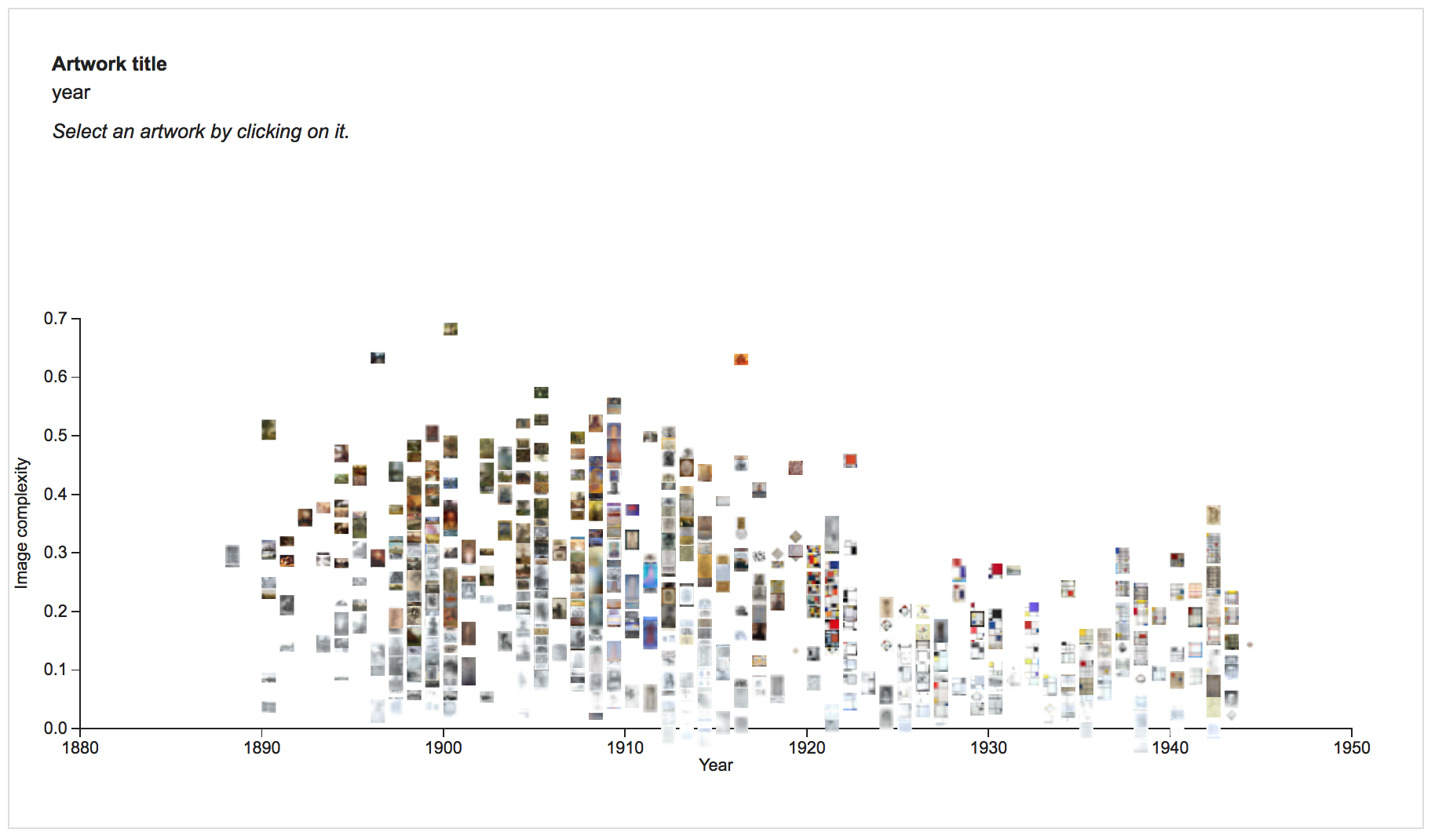

The CryptoPunks are a generative art project comprised of a series of 10k pixelated portraits of punks with proof of ownership stored on the Ethereum blockchain. Matt and John famously released the Punks into the world for free in 2017 as one-of-a-kind digital collectables that anyone could claim. An economy quickly emerged around the characters, with the more rare Punks selling for thousands of dollars.

CryptoPunks has helped to prove out and popularize the application of digital scarcity to digital art on the blockchain as pioneered by projects like Rare Pepe Wallet. Where Chaos Machine took currency born in the physical world and turned it into a digital currency, Matt and John are taking their Punks, born digital, and giving them a new material existence as printed work for this show. It was important to them to communicate that as digital art, physical representations are only artifacts of the genuine digital asset. As John explains:

For this show, we tried to bridge the divide between physical and digital art, while still reinforcing the point that the digital, cryptographic asset represents the true "ownership" of the work, as opposed to the physical print. We did this by including with each print a "paper wallet," which is a set of 12 words that encode an Ethereum address (using the BIP-39 standard). So that it wasn't seen as subordinate to the print, and to have a little fun, the paper wallet was sealed with a custom CryptoPunk wax seal. The buyer can decide to either open the envelope and claim ownership over the Ethereum address that owns the punk, or they can simply leave it sealed, and include it with the print if they resell the work. So, one of the earliest forms of security is brought together with one of the most modern to make these works both physical and digital.

One way to think of these printed representations of the Punks is as a physical proxy for their digital equivalents. The work of another artist in the show, artist Kevin Abosch, has long explored the idea of proxies, first through photographs as proxies for the people and objects captured within them, and more recently, through tokens and tokenization as proxies.

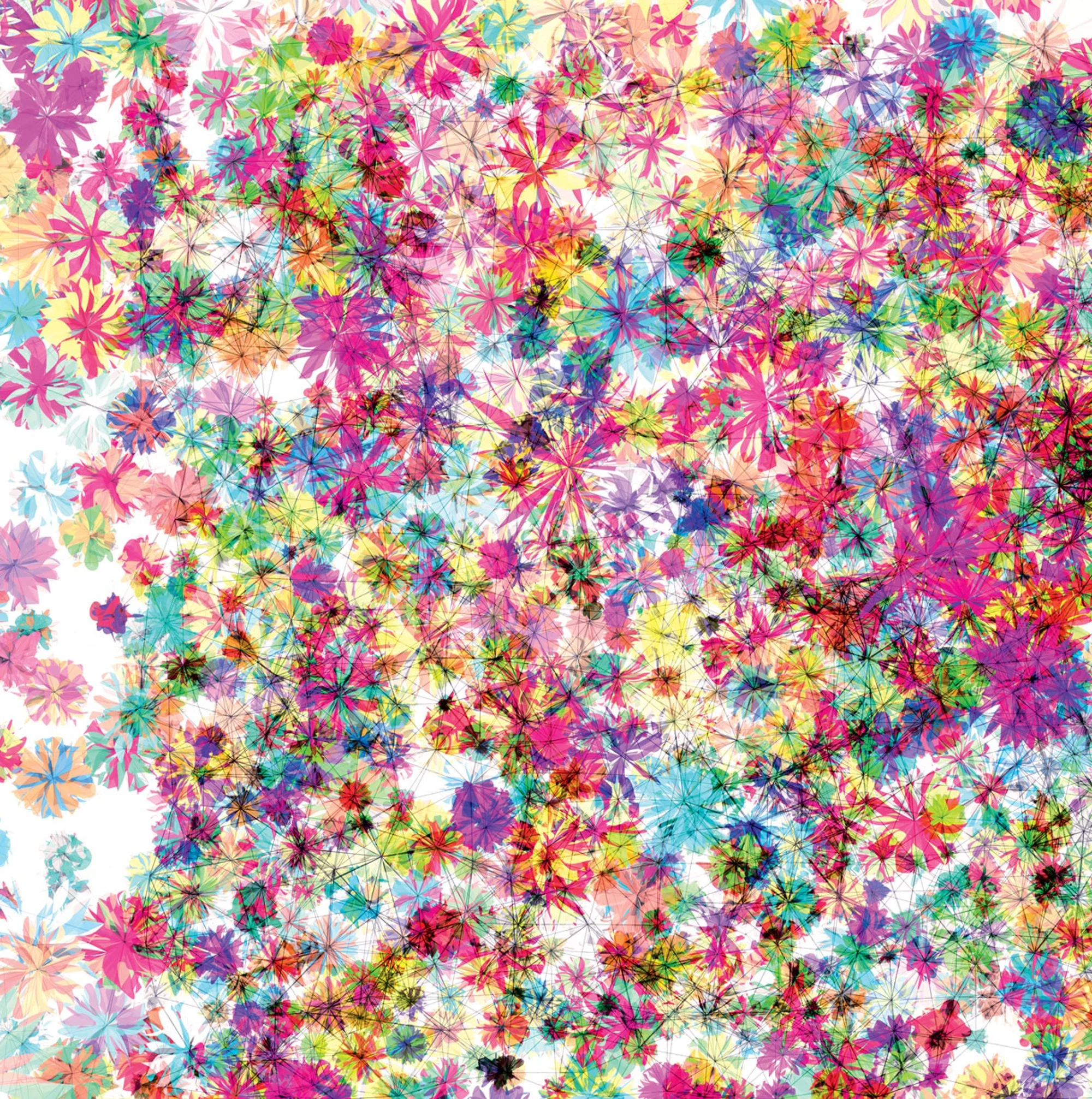

In his work IAMA Coin included in the exhibit, Abosch created 100 physical artworks and a limited edition of 10 million virtual artworks. The physical works are stamped using the Abosh's own blood with the contract address on the Ethereum blockchain corresponding to the creation of the the 10 million virtual works (ERC-20 tokens).

Artist Kevin Abosch harvesting blood as material for his IAMA Coins

In my interview with Abosch last spring, he provided more background and detail on the IAMA Coin project:

My IAMA Coin project really is the culmination of everything I am about: identity, existence, value, human currency. And it's just a function of me being an artist with a bit of success and feeling a bit commodified... as I have said in the press already. And I started to imagine myself as a coin. In fact, I started looking at of all of us as coins, and wondered what that would look like, all of us as coins in the hands of the masses, and wanted to do that in some kind of elegant way. So naturally I started to look at the blockchain.

But still I was thinking, "I'm an artist, I'm not trying to raise money for a company, so I will tokenize myself..." and you saw how I did that - the blood, the physical work, and the virtual work of my IAMA Coin project. It has been a bit of a challenge for some people as to how an ERC20 token itself can be a piece of virtual art, or it is a placeholder for art, whichever you prefer. I think when it comes to blockchain plus art, this would be a rather extreme position.

Abosch’s second work in the exhibition is a collaboration with Ai Wei Wei called PRICELESS. It further explores the idea of proxies and asks the question, “How and why do we value anything at all?” by tokenizing photographs of moments the two artists have shared. Abosch says:

I have been using blockchain addresses as proxies to distill emotional value for some time now, and with Wei Wei, we “tokenized” our priceless shared moments together. Some of these moments on the surface might seem banal while others are subtly provocative, but these fleeting moments like Sharing Tea and Walking In A Carefree Manner Down Schönhauser Allee or Talking About The Art Market are the building blocks of human experience. All moments in life are priceless.

Each priceless moment is represented by a unique blockchain address which is “inoculated” by a small amount of a virtual artwork (crypto-token) we created called PRICELESS (symbol: PRCLS). Only two ERC20 tokens were created for the project, but as they are divisible to 18 decimal places, these works of virtual art could potentially be distributed to billions of people. Furthermore, a very limited series of physical prints were made.

One of the two PRICELESS tokens will be unavailable at any price. The remaining token will be divided into one million fractions of one token and made available to individual collectors and institutions. These artworks of course may be divided into much smaller artworks, as the PRICELESS token is divisible to 18 decimal places. It is not unusual in the art world for large works to be priced higher than similar smaller works; so should a larger fraction of PRICELESS have a higher price than a smaller fraction. One of those peculiar ways we value things — greater size/quantity = greater value. The question is, if one token is priceless and truly unattainable, then how do we value the other token which is made available?

My understanding is that the photographs are not for sale and the physical works are printouts of the wallet address that contain a “nominal amount of PRCLS token.” In this sense, the wallet addresses are a proxy for the photographs, which are in turn a proxy for the moments shared between the two artists.

Printout of a PRICELESS wallet address

As described by Abosch above, there is also a second PRICELESS token which is being distributed and is divisible enough so that everyone on the planet could receive a share.

According to the smart contract, I happen to be one of the first people to receive a share of the token, and I have enough that I can give a fraction to every person on the planet. If you are interested, email me your MyEtherWallet address at jason@artnome.com and I will send you a fraction. As a collector of Abosch’s art, I will warn you he often scrambles traditional value systems so much that you are left uncertain as to what it is you own (if anything) and what that something is worth - and I think that is exactly the way he likes it.

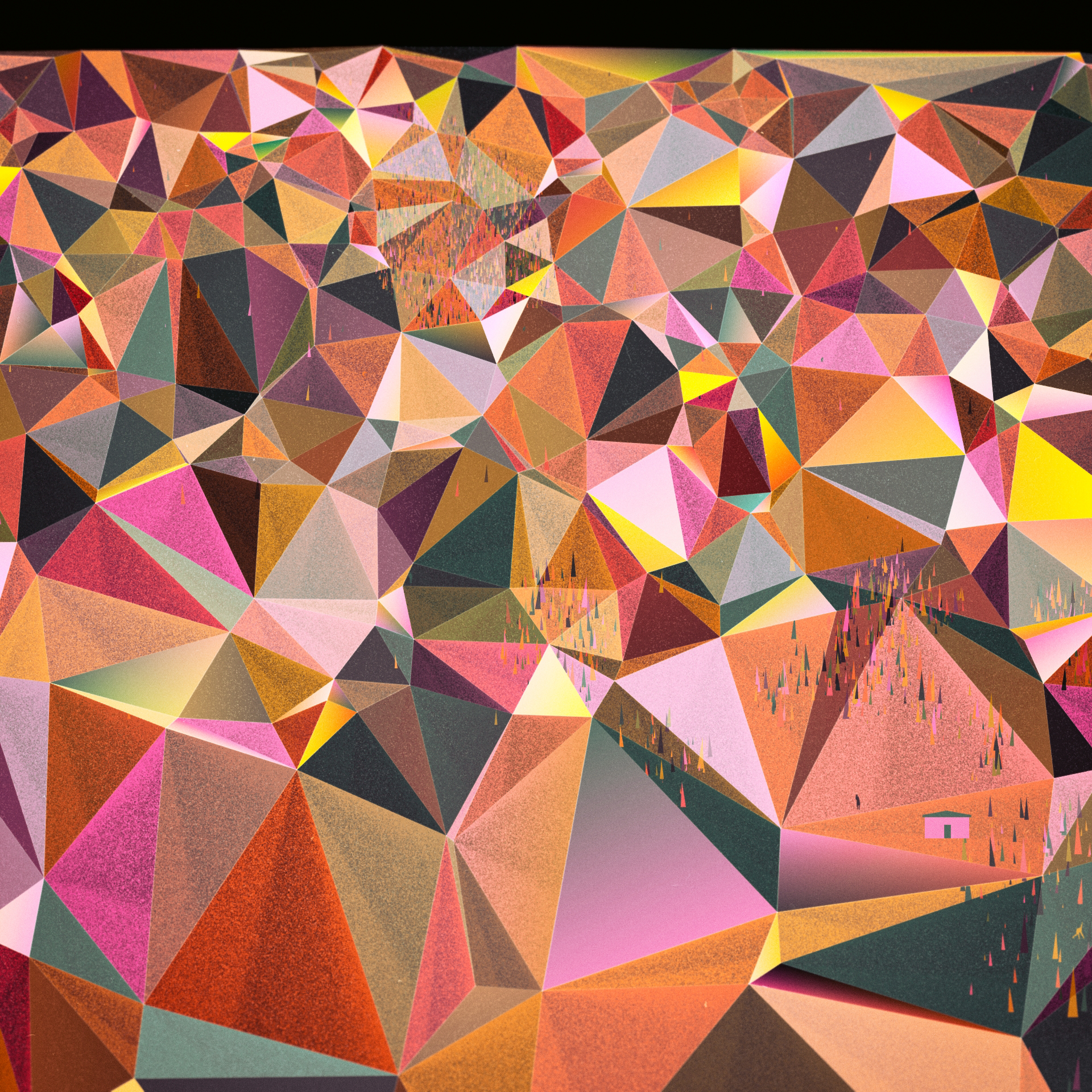

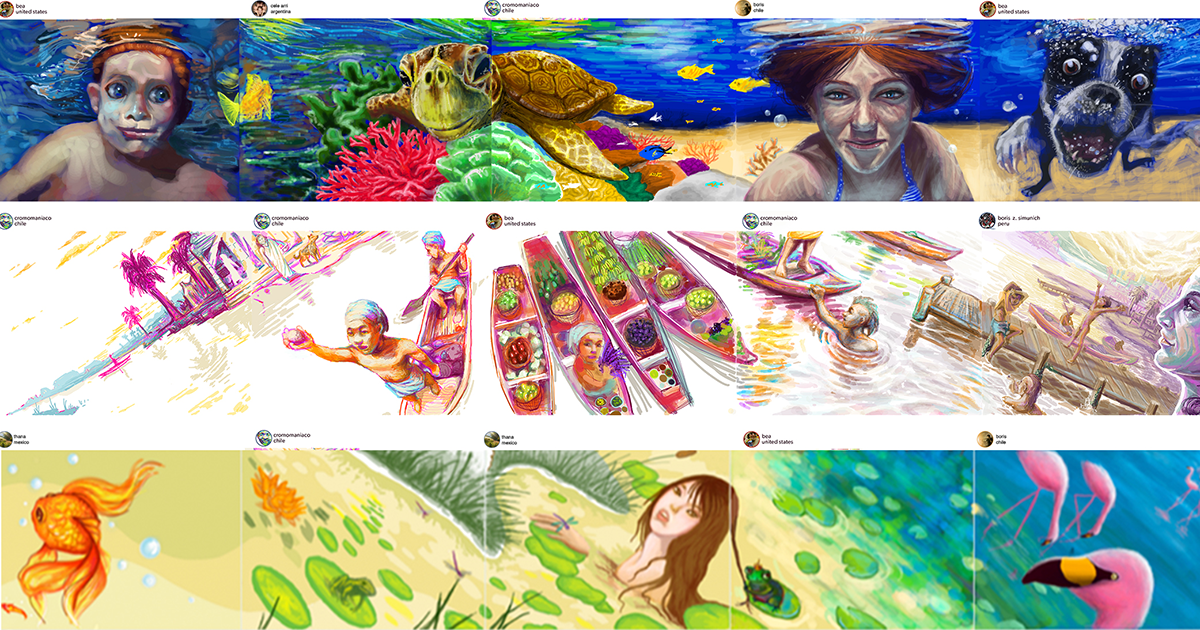

Ai Wei Wei is not the only well-known artist from the more traditional art world exploring the use of blockchain. Renowned artist Eve Sussman who is best known for translating well-known masterworks into large scale re-enactments has teamed up with Snark.art to create a piece called 89 Seconds Atomized.

The work is based on her well-known piece 89 Seconds at Alcázar, a live re-enactment which meticulously creates the moments directly before and after the image portrayed by Diego Velázquez in Las Meninas (1656). The piece debuted at the 2004 Whitney Biennial to great acclaim and can be seen in it’s original form below.

According to Snark.Art:

89 seconds Atomized shatters the final artist's proof of Eve Sussman's acclaimed video 89 seconds at Alcazár into 2,304 unique blocks, to create a new artwork on the blockchain. An experiment in ownership and collective interaction, the piece can be reassembled and screened at will by the community of collectors.

I received a sneak preview of 89 Seconds Atomized at a well-attended blockchain art event hosted by Elena Zavelev and the New Art Academy at NYU this past October where Sussman gave an artist’s talk and presented the work to the audience.

Sussman provides more detail on her motivation to explore the blockchain for her recent piece in the video below.

This project is Snark.art’s first collaboration as part of their mission to “…create a distributed system of art ownership and creation while also offering an entirely new crypto-investment opportunity and point of entry to the blockchain world.” I’m looking forward to following their future artist collaborations.

Blockchain Startups, Tools, and Innovations

Perhaps you are not Ai Wei Wei or Eve Sussman, but you too would like to put your work on the blockchain for better provenance and the opportunity to sell your digital art. What about the rest of us?

There are now a dozen or so blockchain-based art markets that cater to artists of many ability levels and experience. Markets like SuperRare are evolving quickly and have even become a place for traditional auction houses like Christie’s to source talent. The French artist’s collective Obvious that recently sold their Portrait of Edmond Belamy for $450K were contacted by Christie’s after they were discovered on the SuperRare blockchain art market.

I asked the SuperRare folks what it was like to hear that Obvious had been scouted form their market place:

It was exciting and somewhat surreal to see Obvious get picked up by Christies and have such a successful auction, after starting to sell their digital works on SuperRare earlier in the year. It's fantastic to see this much attention on creators who are experimenting with the intersection of art and new technologies, whether AI or blockchain. I think this is just the beginning of a big shift in the way we think about art, value, and the potential of computers to augment human creativity.

In addition to pioneering the lively and active SuperRare market, Pixura, SuperRare’s parent company, has announced they are making it possible for anyone to launch their own market for art and collectibles on the Ethereum blockchain.

With Pixura, the goal is to lower the barrier to entry for building crypto collectible applications. When we launched SuperRare, we got contacted by a lot of creatives, entrepreneurs, and even web developers who wanted a digital asset marketplace for their idea, but didn't have the means to do the blockchain engineering themselves. So we're launching a platform that lets anyone deploy a digital asset marketplace in minutes, without writing any code. The possibilities of this nascent technology is super inspiring, and we're excited to see what people build on it.

This is huge, and I think it gets at what most artists really want: a turn-key, Shopify-style solution for selling their own digital art and collectibles on the blockchain. From early on, most of the artists I spoke with were concerned that their carefully crafted personal brand might be thrown off if they were just tossed in with dozens of other artists at random on a catch-all marketplace. For example, if I paint impressionistic floral still lifes and you paint bloody skulls, I may not want my work to be juxtaposed next to your work (or maybe I do?), but existing blockchain marketplaces do not give artists that level of control.

I personally can’t put to rest the idea of launching an Artnome gallery for digital art built on the Pixura platform. I’d like to launch a heavily curated digital gallery with a small number of works by an even smaller number of artists. I’d want my gallery to celebrate artists as heroes - the way I read about them and experienced them when I was growing up. In an age when it is no longer popular to think of artists as geniuses, I still see great art and artists as transcendent and worthy of our greatest admiration. To be honest, I miss the romantic myth-making put behind artists like the abstract expressionists that made them feel so much larger than life to me. Curation, of course, flies in the face of blockchain and decentralization - but we already have several great distributed blockchain art markets, and I want to build a house of worship for amazing contemporary digital artists, dammit. I’ll get off my soap box - but feedback is welcome here, both for and against.

One thing that would hold me back from building a blockchain market is how complicated it still is for the average person to grasp blockchain. Getting your first cryptocurrency requires connecting your bank account and downloading third-party browser plugins like MetaMask in order to transact. While a recent Twitter poll I took with 193 respondents suggests almost 75% of people are open to collecting digital art on the blockchain, most people would agree that user experience is the number one thing slowing down new user adoption of cryptocurrency and collectibles.

Twitter poll taken from my @artnome account

Luckily, startups like Portion.io are investing heavily in UX (user experience design) to help streamline the process. Portion is a blockchain Dapp that allows anyone to be their own auction house on the blockchain. It is still early in their development, but they officially launched their beta last month with a collection of digital sneakers from artist Robb Harskamp. The first thing I noticed when buying my Harskamp Air Jordan 3 Retro Tinker from Portion is that I did not need MetaMask - and I didn’t miss it.

Air Jordan 3 Retro Tinker, Robb Harskamp - 1/1, Artnome digital art collection

While those who have come to like MetaMask can either "safely generate a new wallet" or use "MetaMask when the functionality is built in", Portion has effectively removed a step for new buyers, making it easier to get started. I spoke to Portion CEO Jason Rosenstein about the importance of simplifying UX for blockchain markets:

Currently, there are as many crypto users as internet users in the year 1994. For blockchain projects to truly take off, I believe the key will be taking the cryptic out of crypto. There will come a point when people won’t need to know the underlying technology of a particular application is interacting with the blockchain. For example, when you send an email, not many people give a shit about the amazing underlying TCP/IP protocol. For crypto projects to succeed in the future, they must cater to the general population by improving UX/UI and investing in R&D to reduce barriers to entry.

Interface for the new Portion.io Dapp

Though Portion.io launched with a digital marketplace, their plan is to quickly move into the physical space, as well, allowing anyone to auction digital and physical goods with the many advantages that come with transacting via cryptocurrency.

Indeed, the physical art market dwarfs the relatively new and niche market for collecting digital art. This was never more apparent to me than at the social hour after Christie’s blockchain conference in London. Everyone there worked in the art trade in one form or another, and they were all hungry to learn how blockchain related to the trade for art and other physical luxury goods.

The BAC (Blockchain Art Collective) has an excellent head start on building out a solution for authentication and tracking of physical art that combines IoT (internet of things) and blockchain technologies. I spoke with Jacqueline O'Neill, executive director, about what makes BAC unique:

Blockchain Art Collective has chosen to tackle the physical art space first and foremost, as our blockchain and trusted IoT solutions have been in development with our tech partner Chronicled since 2014, and they bring a lot of unprecedented value to the art world.

What anyone from an artist to a gallery to an auction house to an art logistics company should understand is that we now have the capacity to create the same level of physical scarcity - which relies on a variety of security-related, technological features made possible by blockchain and trusted IoT - for physical art in the way we are seeing digital scarcity for digital art.

This one-to-one, tamper-evident, and encrypted physical-digital link improves the not-so-unfamiliar barcoding system for managing any volume of art assets by combining the role of the artist's signature, a physical or digital certificate of authenticity, and a physical or digital catalogue raisonné into a single, secured identity that can stay with an artwork over the course of its life.

Additionally, we can now connect that unique artwork with a rich digital life that protects its authenticity, tracks its provenance, and unlocks new vehicles for artists and arts institutions to monetize their artworks.

Blockchain Art Collective tagging sticker

A large part of what I find compelling about BAC is that it was spun out of Chronicled, who have been deploying decentralized supply chain ecosystems and building protocol-driven solutions to enhance global trade across key industries since 2014. That experience and know-how combined with O’Neill’s art background and passion for the solution give it a real shot of catching on as a widely used solution for physical art.

Conclusion - Is Art Blockchain’s Killer App?

So what would it look like if art was Blockchain’s killer App? What would it take to successfully integrate blockchain into the art world and solve real-world problems? We would probably want to see some of the biggest institutions like Christie’s experimenting in a high-profile way with blockchain. Check. We might also want to see some of the world’s most influential living artists, people like Ai Wei Wei, experimenting with blockchain as subject matter and and as a medium. Check. And given it is still the early days, we’d want an army of startups and creative technologists working around the clock on R&D to improve and invent new solutions. Check.

I have been trying to tell people for the better part of a year now that the blockchain use case for art has very little to do with the cryptocurrency craze of late 2017. The popular opinion among most innovators in this space is that the volatility and press that came with the bull market may have done more harm than good for those trying to build out actual solutions. So perhaps we should not be surprised at all by the signs of growth and strength in blockchain and art. It may not be getting as much press as a few months ago, but I would not take your eye off the blockchain and art space.