I’m working on a longer article about democratizing AI for artists, but in the process of writing that article, I started using Runway ML and Jason Antic’s deep learning project DeOldify to colorize old black-and-white photos of artists - I couldn’t stop. So I decided to share an “eye candy” article as a preview of my longer piece.

When I was growing up, artists, and particularly twentieth century artists, were my heroes. There is something about only ever having seen many of them in black and white that makes them feel mythical and distant. Likewise, something magical happens when you add color to the photo. These icons turn into regular people who you might share a pizza or beer with.

That distance begins to collapse a bit and they come to life. The Picasso photo above, for example, always made me think of him as a this cool guy who hung out in his underwear all the time. But the colorized version makes him seem a bit frail and weak, and maybe even a tinge creepy.

Photos of artist couples, in general, seem to really hammer home their humanity. I think it is because so many photos of artists seem staged or posed. But when we catch them with their spouse or lover, they are their relaxed selves for a candid moment. You can almost imagine inviting them over to play cards.

Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock

Joan Miro and Pilar Juncosa

Alfred Stiglietz and Georgia O’Keefe

William and Elaine De Kooning

Other photos feel even more magical and distant after the deep learning auto colorization. The image below with Frida Kahlo crouching next to a deer, for example (my favorite), feels somewhat otherworldly. Likewise with the famous photo of Salvador Dali flying through the air and Yayoi Kusama photographed with her spotted horse.

Frida Kahlo

Salvador Dali

Yayoi Kusama

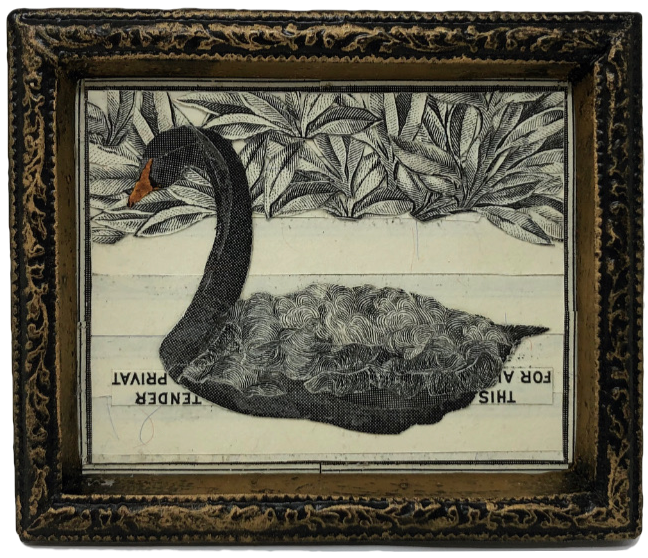

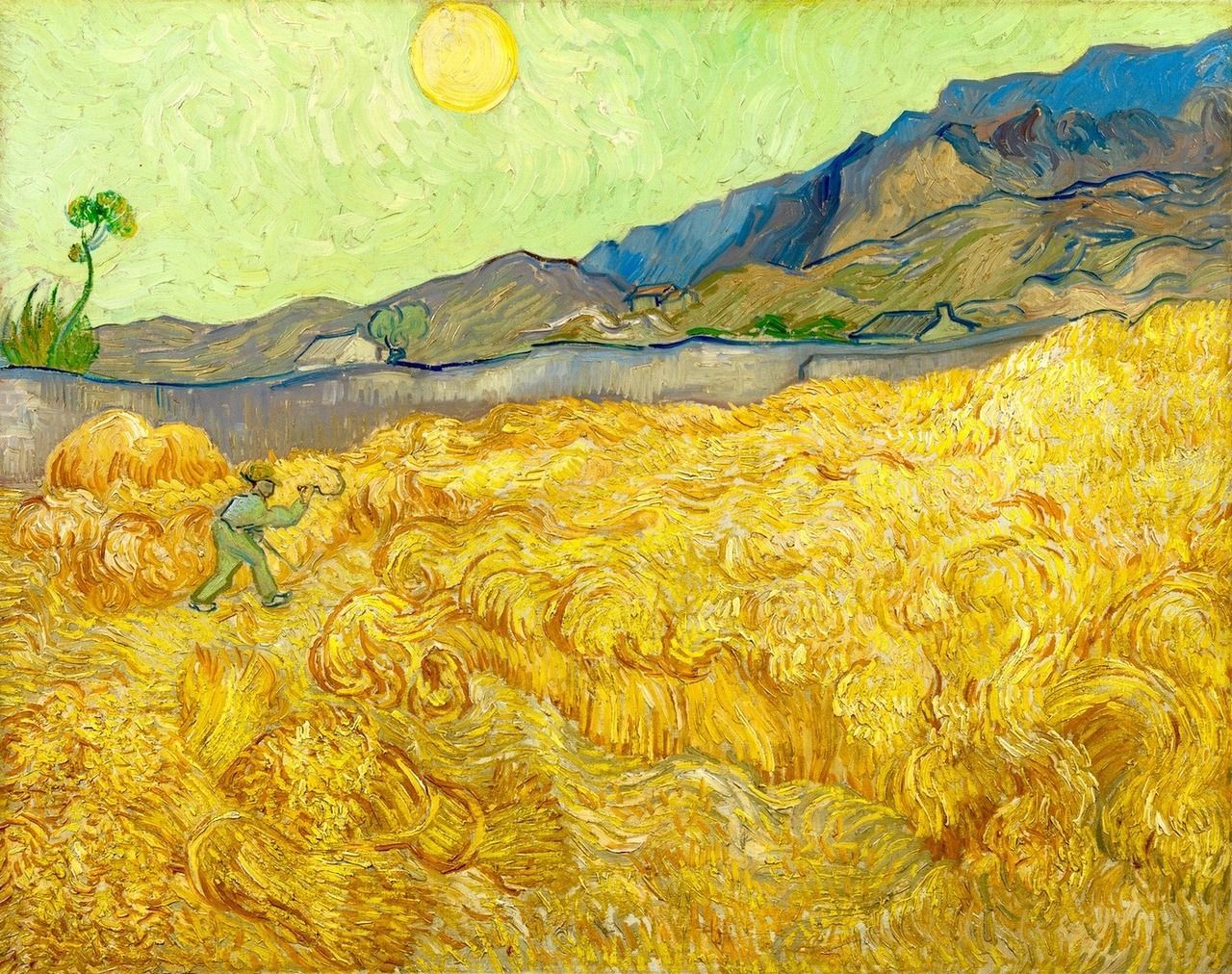

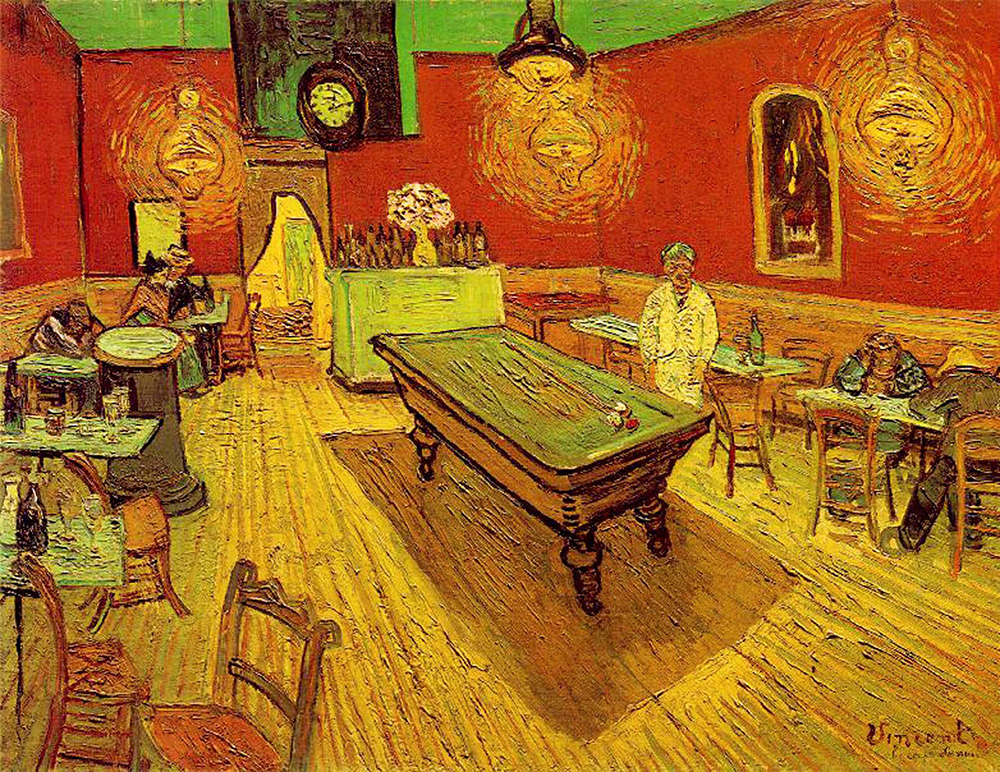

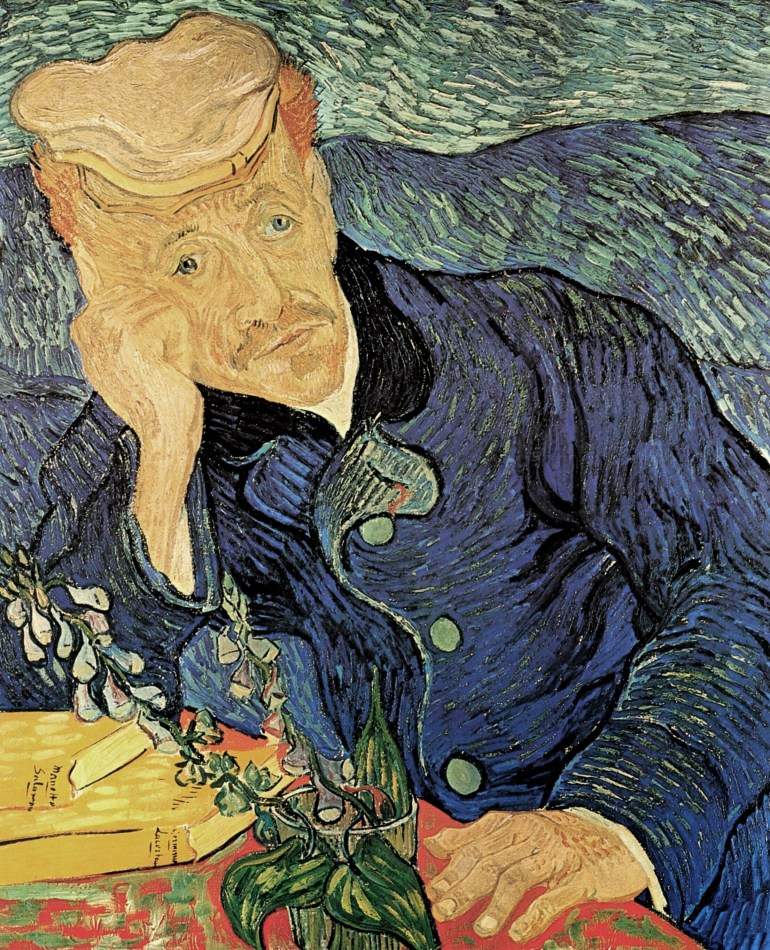

I also really enjoy watching the algorithm trying to figure out how to colorize the actual paintings from the artists. It turns James Ensor into a bit of a pale zombie, but has him painting in a neon palette fit for a blacklight. Kandinsky’s palette shifts almost entirely to purples and blues and takes on an almost tribal feel.

James Ensor

Wassily Kandinsky

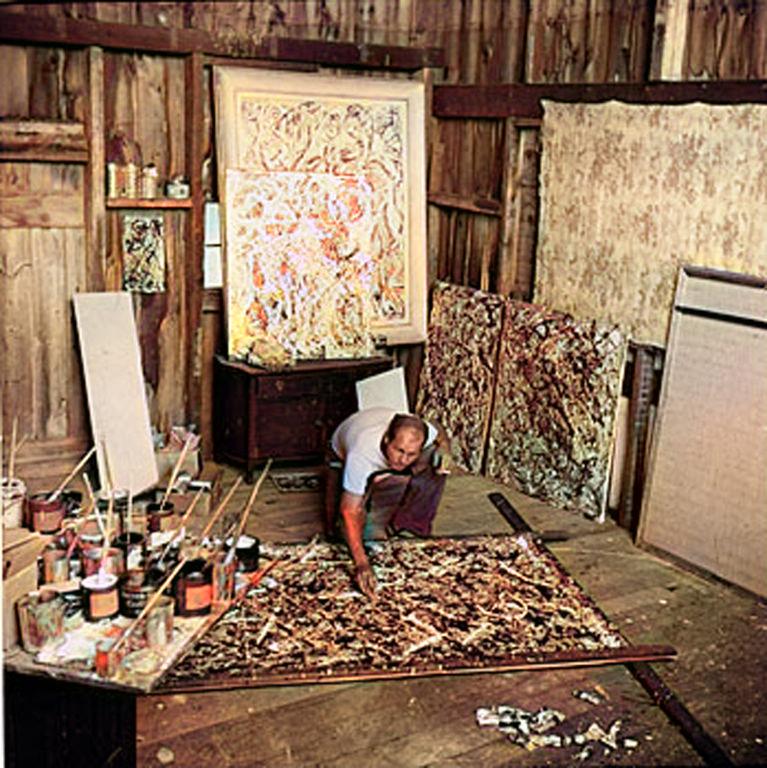

Jackson Pollock

Georges Braque

Raul Houseman and Hanna Hoch

There are some known issues with AI and machine learning being overly trained on white people, and thus struggling with properly representing people with nonwhite skin tones. You can see this a bit in the colorized image of Picasso in which he appears more pale than the olive/bronze tone we are used to seeing in known color photos. Jason Antic, the developer working on DeOldify takes this very seriously, and just yesterday tweeted the following:

On the question of skin tone bias in DeOldify: We take this issue seriously, and have been digging into it. We're going to be overhauling the dataset to make sure it's driving more accurate decisions in the next few weeks. Overall, there seems to be a red bias in everything.

"Everything" includes ambiguity in general object detection. It can even be seen in Caucasian colorings (see example below- left is original, right is DeOldify). So overall it seems that DeOldify needs a better dataset than just ImageNet. We're prioritizing it -now-.

Example of bias toward red from Jason Antic Twitter stream

That being said, it's a challenging problem and it'll be hard to verify. Everybody is different, so making this work for all cases will probably be something we'll need years to perfect. So please keep an eye out for updates and keep trying it out for yourself!

That said, it does a reasonable job of not “whitewashing” non-Caucasian artists, considering it has a ways to go before perfecting skin tones, regardless of color.

Jacob Lawrence

Alma Thomas

Wifredo Lam

Rufino Tamayo

Aaron Douglas

Kazuo Shiraga

Isamu Noguchi

The algorithm also seemed to struggle with the oldest images. This makes sense to me given there is less fidelity, and therefore, less input to guide the algorithm. With less guidance the algorithm sometimes has to get creative as with the Monet photo below.

Claude Monet

Paul Cézanne

August Rodin

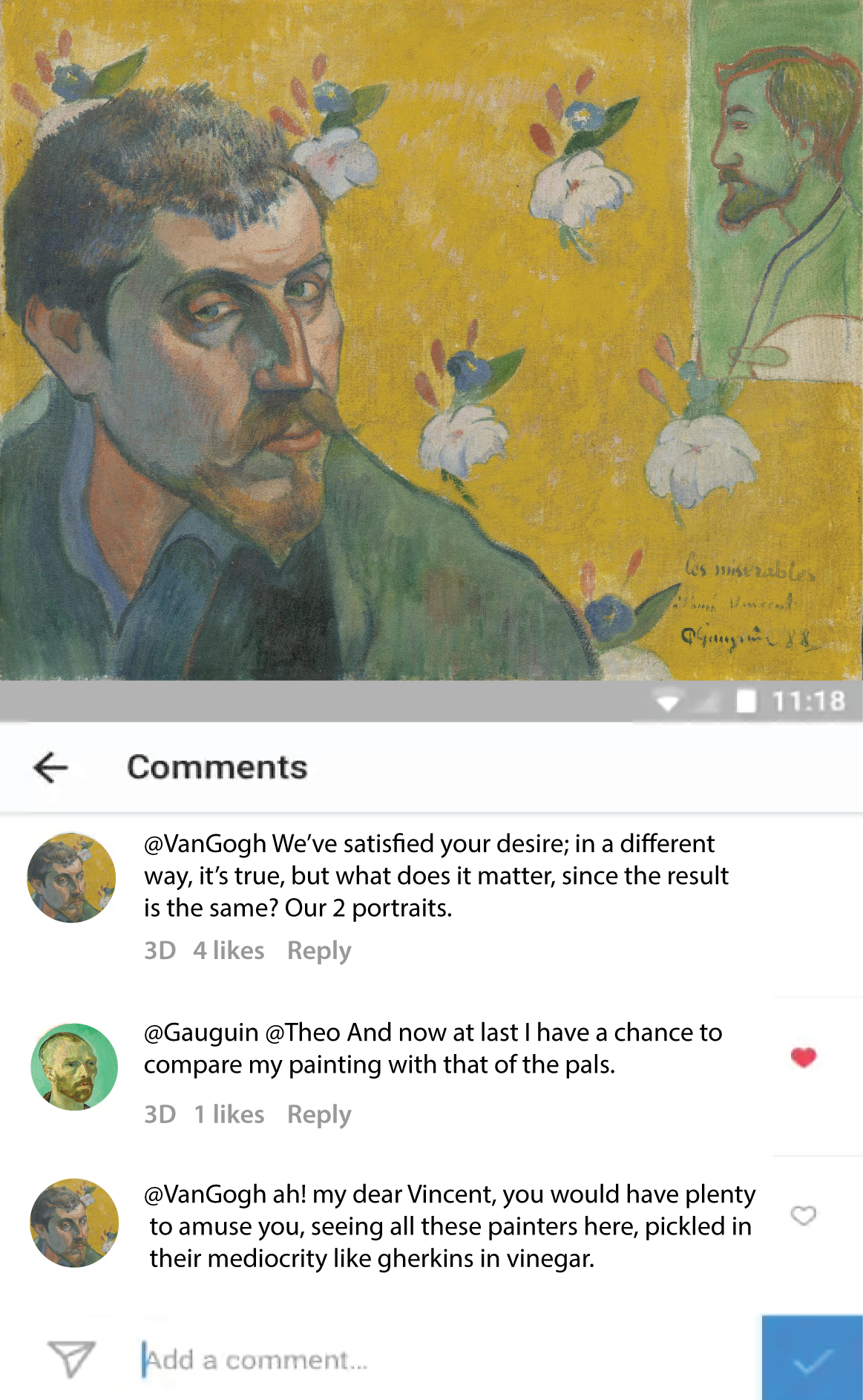

Paul Gauguin

Many of my favorite DeOldified photos are the ones that show artists we are familiar with but either rarely or never have seen photographed in color.

Egon Schiele

Gustave Klimt

Edvard Munch

Leonora Carrington

Hilma af Klint

Piet Mondrian

Henri Matisse

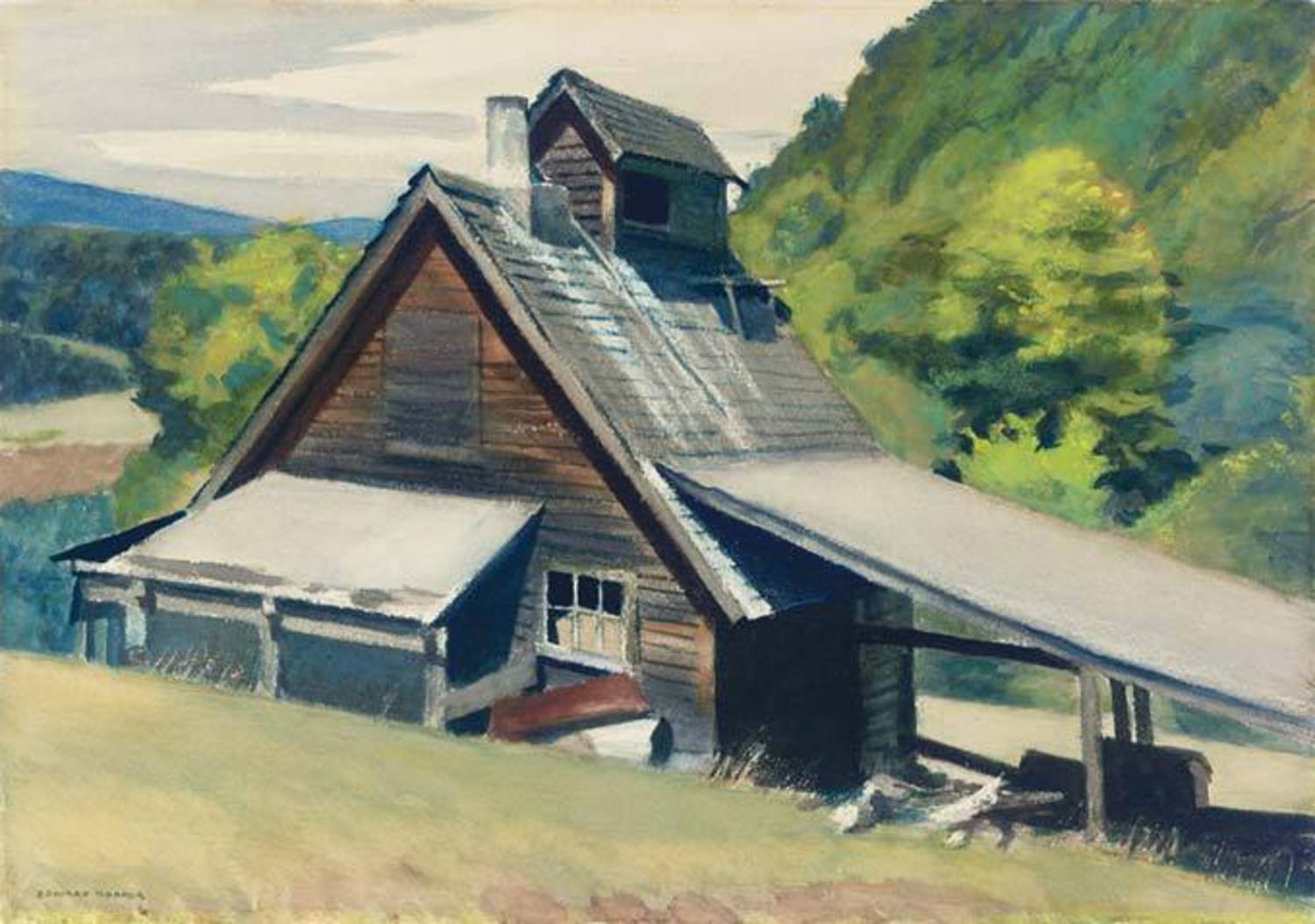

I also really enjoy the photos of the artists in their studios and at work. This younger looking Francis Bacon photo is among the most convincingly colorized photos in the batch I converted.

Francis Bacon

Alice Neal

Agnes Martin

Helen Frankenthaler

Robert Motherwell

Bridget Riley

Louise Bourgeois

Barbara Hepworth

Hans Hofmann

Mark Rothko

Jean Dubuffet

Giorgio de Chirico

Frank Auerbach

Alberto Giacometti

Eva Hesse

Louise Nevelson

Hope you enjoyed seeing these artists in color as much as I did. In the next article, the one I set out to write when I got distracted, I will go into more detail on Runway ML and how it is making these remarkable new AI tools accessible to everyday artists and designers.